September 17, 2024

By Donatas Murauskas

It is not just the individual restriction of rights that matters—the broader context in which they exist is equally crucial. This is the key lesson from the second review of Ms. Ždanoka’s attempts to overcome the restrictions on her candidacy for Parliamentary elections in Latvia. The recent judgment in Ždanoka v. Latvia (No. 2) emphasises the importance of considering the wider context when applying human rights provisions. It also underscores the growing significance of constitutional self-defence as a legitimate basis for restricting human rights, especially in light of the recent challenges in terms of States’ territorial integrity, democratic order and national sovereignty and security.

Ždanoka’s second case is an important development of application of Art. 3 of Protocol No. 3 in at least two directions. First, the distinction between permissible restrictions to stand for elections in connection with particular ‘loyalty to the State’ in contrast to politically motivated ‘loyalty to the government’ (see Tănase v. Moldova [GC]) is crucial. Second, the development concerning the procedural nature of Art. 3 of Protocol No. 1, including safeguards against arbitrariness in the electoral process (see Ždanoka v. Latvia [GC]). I focus more on the first one in this post.

Ms Ždanoka was an active member of the Communist Party of Latvia (CPL) since 1971. On 21 August 1991 Latvia restored its independence and outlawed the Communist Part. According to section 5(6) of the Latvian Parliamentary Elections Act 1995, individuals who had ‘actively participated’ in the Communist Party after 13 January 1991 may not stand as candidates in elections or be elected to Parliament.

Ms Ždanoka was not allowed to stand in parliamentary elections on this basis in 1998 and 2002. The Grand Chamber of the Court held that in 2006 that restriction was neither arbitrary nor disproportionate, finding no violation in its Ždanoka v. Latvia judgment. In 2017 Ms Ždanoka sought a review of the compatibility of section 5(6) of the Parliamentary Elections Act with the Constitution. The Constitutional Court found the provision constitutional on 29 June 2018. The Constitutional Court underlined that the aim of the relevant provision is to protect the democratic State order, national security and the territorial unity of Latvia. The Constitutional Court narrowed the allowed reasons to restrict participation in the election to (i) having endangered Latvian independence and the principles of a democratic state governed by the rule of law and (ii) continuing to endanger Latvian independence and the principles of a democratic state governed by the rule of law at the time of application.

On 21 August 2018 the Central Electoral Commission adopted a decision to strike the applicant’s name out of the list of candidates of the political party Latvian Union of Russians participating in the parliamentary elections of 6 October 2018. The Central Electoral Commission relied on the same section 5(6) of the Parliamentary Elections Act, referring also to the interpretation of this provision by the Constitutional Court in its judgment of 29 June 2018.

Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 provides that ‘The High Contracting Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature.’

According to the Court’s case law, Contracting States enjoy considerable latitude in establishing criteria for eligibility to stand for election, and, in general, they may impose stricter requirements in this context than those imposed for eligibility to vote (Tănase v. Moldova [GC], § 156). However, it is ultimately for the Court to determine whether the requirements of Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 have been met.

The Court must ensure that the restrictions imposed do not curtail the right in question to such an extent that its essence is impaired, or it becomes ineffective; that the restrictions pursue a legitimate aim; and that the means employed are not disproportionate. Such restrictions must not hinder ‘the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature’ (see Mathieu-Mohin and Clerfayt v. Belgium [Plenary], § 52).

Ms. Ždanoka’s saga began long ago, which is significant considering the central argument of this text—that human rights violations are context-dependent. In 2006, the Grand Chamber of the ECtHR found that, given Latvia’s historical and political context, the statutory restriction imposed on the applicant was neither arbitrary nor disproportionate, and that her rights under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 had not been violated.

However, the Court added a particularly important passage:

‘135. It is to be noted that the Constitutional Court observed in its decision of 30 August 2000 that the Latvian parliament should establish a time-limit on the restriction. In the light of this warning, even if today Latvia cannot be considered to have overstepped its wide margin of appreciation under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1, it is nevertheless the case that the Latvian parliament must keep the statutory restriction under constant review, with a view to bringing it to an early end. Such a conclusion seems all the more justified in view of the greater stability which Latvia now enjoys, inter alia,by reason of its full European integration […]. Hence, the failure by the Latvian legislature to take active steps in this connection may result in a different finding by the Court […].’

The Grand Chamber’s judgment left the non-violation decision conditional, shifting the burden towards the justification of the continued restrictions on individuals who may pose a threat to the state’s order, national security, or Latvia’s territorial integrity during ongoing reviews of such measures. According to the Grand Chamber, these reviews should take into account Latvia’s stability, specifically the broader context of its developing democracy, which is now integrated into key European and Trans-Atlantic organisations.

Although Ms. Ždanoka had successfully been elected as a member of the European Parliament, she once again sought to participate in the national parliamentary elections. After her candidacy was rejected, the Constitutional Court took up the case, and in 2018 issued a judgment that considered the previous Grand Chamber ruling in the Ždanoka case. The Constitutional Court examined, among other factors, whether the restriction remained necessary, thoroughly reviewing its justification. This brought us to Ždanoka v. Latvia (No. 2).

The Court recapped its case-law concerning the duty of loyalty that may be required from both current and prospective members of Parliament established in Tănase judgment. Second, the Court underlined positive obligations of procedural nature under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 that oblige member states to establish a domestic system for the effective examination of individual complaints and appeals in matters concerning electoral rights.

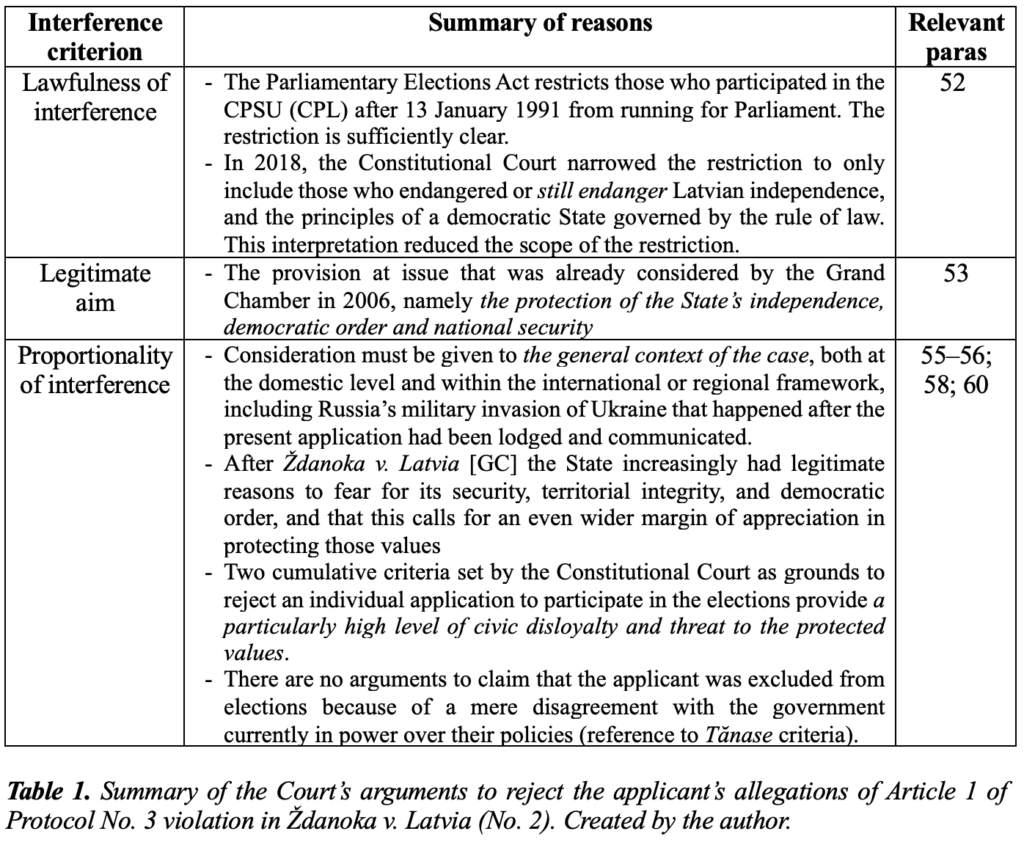

The Court then conducted its analysis of individual circumstances, considering whether the interferences with applicant’s rights under Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 met the requirements of lawfulness, pursued a legitimate aim, and were proportionate to that aim. I summarised the Court’s arguments regarding these three elements in the following table.

The Court heavily relied on the Latvian Constitutional Court judgment that grounded the restriction at issue in Ždanoka (No. 2). In its 2018 decision the Latvian Constitutional Court underlined the importance to consider the status of an individual subject to the restriction, namely, whether the person is still a threat to Latvian democracy. As Melnika and Senders underline, ‘the Constitutional Court strongly emphasized that for a big part of the Latvian society democracy is not yet a self-evident value – the sustainability of democracy can still be threatened.’ The authors refer to the concept of ‘militant democracy’ proposed by K. Loewenstein that influenced the development of ‘democracy capable of defending itself’ notion in the case-law of the ECtHR.

It is difficult to overstate the growing importance of ‘militant democracy’ (an international law concept) and ‘constitutional self-defence’ (a constitutional law concept) in recent years. It’s no longer surprising to hear about Russia’s disinformation campaigns targeting the 2024 U.S. presidential elections. Should a democratic state respond to internal threats? What tools can it use while still adhering to fundamental rights standards? These are some of the conceptual questions that are increasingly discussed in constitutional and international law scholarship.

Militant democracy, as a legal concept, refers to the importance of a democratic state to be able to swiftly react to potential inner threats by ‘curbing political participation of the most extreme political actors, [as it is then] possible to prevent their abuse of democracy’. The major problem with ‘militant democracy’ is the potential of its adverse effects on democracy in the long run. The difficulty lies in determining whether a person is truly an ‘enemy’ of democracy to the extent that restricting their rights is necessary, and in the potential long-term establishment of ongoing measures against such internal enemies.

In the Ždanoka (No. 2), the Court navigated the unclear boundaries between the importance of preserving human rights and the challenge of maintaining constitutional order (not for the first time, but among the first in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine). Once again, the Court demonstrated its sensitivity to the broader context that may objectively influence how states address certain fundamental rights issues. Although the application was submitted before Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022, the Court’s explicit reference to developments occurring after the restriction of the applicant’s rights – ‘the Court cannot ignore the fact that on 24 February 2022 Russia launched a military invasion of Ukraine, following which, as a result of a procedure initiated under Article 8 of the Statute of the Council of Europe, the Russian Federation ceased to be a member State as from 16 March 2022’ (para 55) – illustrates how willing it is to incorporate contextual background into its deliberations on individual cases.

While commenting on the 2018 judgment of the Latvian Constitutional Court, Madara and Senders questioned whether ‘the argument of threats to the newly established democracy caused by the resurgence and promotion of communist ideas, which might lead to the restoration of a totalitarian regime,’ recognised in the 2006 decision, still applies. In this regard, we may never know the exact answer, as the Russian aggression in 2022 has altered the broader context of European security, particularly for bordering states.

The Grand Chamber’s conditional clause in the Ždanoka case required Latvia to act diligently and assess the actual necessity of the restriction in question. This clause effectively balanced the applicant’s rights with national interests, allowing the state to maintain preventive measures against real threats to its existence. It also gave the Court more flexibility to account for broader destabilising factors in Europe, such as those arising from Russian aggression in 2022.

This judgment is another step in the development of the Court’s doctrine on a democracy capable of defending itself. The Court’s approach is shaped in the context of weakened European stability and includes cases that similarly address restrictions on fundamental rights based on potential internal threats (for example, Kirkorov v. Lithuania) and cases related to the development of constitutional stability and identity as values that need to be safeguarded (see, for example, Savickis v. Latvia). The Court’s case law on developing these constitutional self-defence-related doctrines resembles dancing on thin ice over deep waters, compromising the universality of human rights or sacrificing national interests by undermining the principle of subsidiarity. Which one should prevail in the turbulent European landscape?

In Ždanoka v. Latvia (No. 2), the Court demonstrated the concept that ‘it does not operate in a vacuum’. The Court balanced its focus between the restriction of individual rights and the broader context in which the individual acted. The endorsement of the constitutional self-defence doctrine in Ždanoka v. Latvia (No. 2) marks another step in the complex judicial dialogue between the ECtHR and national constitutional courts, as they seek an optimal balance between the equal protection of fundamental rights and the need to maintain a functioning constitutional order and state stability. The Court’s decision represents a further, nuanced step in endorsing constitutional self-defence, by setting limits through the procedural obligation to thoroughly assess all individual and contextual or regional circumstances.