October 19, 2015

By Dirk Voorhoof *

On 17 December 2013 the European Court of Human Rights had ruled by five votes to two that Switzerland had violated the right to freedom of expression by convicting Doğu Perinçek, chairman of the Turkish Workers’ Party, for publicly denying the existence of the genocide against the Armenian people (see our blogs on Strasbourg Observers and ECHR-Blog, 7 and 8 January 2014). The Grand Chamber has now, on 15 October 2015, in a 128 page judgment, confirmed, by ten votes to seven, the finding of a violation of Article 10 ECHR.

On 17 December 2013 the European Court of Human Rights had ruled by five votes to two that Switzerland had violated the right to freedom of expression by convicting Doğu Perinçek, chairman of the Turkish Workers’ Party, for publicly denying the existence of the genocide against the Armenian people (see our blogs on Strasbourg Observers and ECHR-Blog, 7 and 8 January 2014). The Grand Chamber has now, on 15 October 2015, in a 128 page judgment, confirmed, by ten votes to seven, the finding of a violation of Article 10 ECHR.

Facts

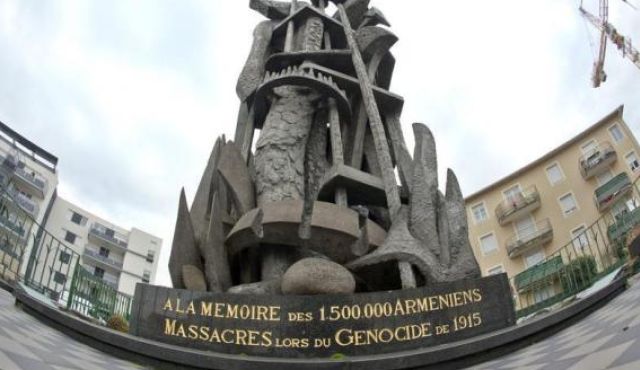

At several occasions in public speeches, Perinçek had described the Armenian genocide as “an international lie”. The Swiss courts found that Perinçek’s denial that the Ottoman Empire had perpetrated the crime of genocide against the Armenian people in 1915 and the following years, was in breach with Article 261bis § 4 of the Swiss Criminal Code. This article punishes inter alia the denial, gross minimisation or attempt of justification of a genocide or crimes against humanity. According to the Swiss courts, the Armenian genocide, like the Jewish genocide, was a proven historical fact. Relying on Article 10 of the European Convention, Perinçek complained before the Strasbourg Court that his criminal conviction and punishment for having publicly stated that there had not been an Armenian genocide had breached his right to freedom of expression.

The Chamber judgment of 17 December 2013

In its Chamber judgment, the Court’s second section reiterated that the free exercise of the right to openly discuss questions of a sensitive and controversial nature was one of the fundamental aspects of freedom of expression and distinguished a tolerant and pluralistic democratic society from a totalitarian or dictatorial regime. According to the Chamber, the rejection of the legal characterisation as “genocide” of the 1915 events was not such as to incite hatred or violence against the Armenian people. It found that Perinçek had engaged in speech of a historical, legal and political nature which was part of a heated debate, and that historical research is by definition open to discussion and a matter of debate, without necessarily giving rise to final conclusions or to the assertion of objective and absolute truths. The Chamber took the view that the Swiss authorities had failed to show how there was a social need in Switzerland to punish an individual on the basis of declarations challenging the legal characterisation as “genocide” of acts perpetrated on the territory of the former Ottoman Empire in 1915 and the following years. In conclusion, the Chamber pointed out that it had to ensure that the sanction did not constitute a kind of censorship which would lead people to refrain from expressing criticism as part of a debate of general interest, because such a sanction might dissuade contributions to the public discussion of questions which were of interest for the life of the community. It found that the grounds given by the national authorities in order to justify Perinçek’s conviction were insufficient and that the domestic authorities had overstepped their narrow margin of appreciation in this case in respect of a matter of debate of undeniable public interest. Accordingly there had been a violation of Article 10.

The referral to the Grand Chamber and third-party comments

The Chamber judgment was, as expected, highly controversial and the Swiss Government requested that the case be referred to the Grand Chamber. On 2 June 2014 the panel of the Grand Chamber accepted that request. In the Grand Chamber proceedings, third-party comments were received from the Turkish Government, who had exercised its right to intervene in the case (Article 36 § 1 of the Convention). Third-party comments were also received from the Armenian and French Governments (Article 36 § 2). Furthermore, third-party comments were received from the Switzerland-Armenia Association; the Federation of the Turkish Associations of French-speaking Switzerland; the Coordinating Council of the Armenian Organisations in France (“CCAF”); the Turkish Human Rights Association, the Truth Justice Memory Centre and the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies; the International Federation for Human Rights (“FIDH”); the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism (“LICRA”); the Centre for International Protection and a group of French and Belgian academics. It was at least a peculiar event to see the Turkish Government vehemently arguing in favor of a strong protection of freedom of expression and insisting that the European Court of Human Rights should fulfill its supervisory role in strictly scrutinizing and assessing the “pressing social need” of the interference by the Swiss authorities in this matter.

With some recent judgments in mind in which the ECtHR, and especially the Grand Chamber, left a (very) wide margin of appreciation to the members states in relation to the assessment of the pressing social need justifying interferences with the right to freedom of expression (Mouvement raëlien suisse v. Switzerland, Animal Defenders International v. United Kingdom and Delfi AS v. Estonia) and taking into account the actual challenge in European democracies to effectively prevent and combat hate speech, it had become doubtful whether the Grand Chamber would confirm the finding of a violation of Article 10 in the Perinçek case.

The judgment of the Grand Chamber of 15 October 2015

The Grand Chamber’s assessment and argumentation, the voting and the robust concurring and dissenting opinions give evidence that indeed there is fierce controversy within the European Court of Human Rights on how to apply the Convention in the case at issue. By ten votes to seven, the Grand Chamber confirmed that there has been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention. Seven judges however, including the president of the Court, claim vigorously that the conviction of Perinçek in Switzerland did not amount to a breach of his right to freedom of expression. Four of them also argued that Article 17 (abuse clause) should have been applied in this case.

The dissenting judges emphasize “that the massacres and deportations suffered by the Armenian people constituted genocide is self-evident. The Armenian genocide is a clearly established fact. To deny it is to deny the obvious”, immediately admitting however that this is not the (relevant) question in the case at issue. According to the dissenting judges the real issue at stake is

“whether it is possible for a State, without overstepping its margin of appreciation, to make it a criminal offence to insult the memory of a people that has suffered genocide”

And they confirm that in their view, this is indeed possible. The argumentation of the dissenting judges clearly reflects the tendency to narrow down the supervisory role of the European Court and to accept that criminalising free speech and the participation in public debate, is a matter falling within the State’s margin of appreciation.

It is extremely relevant to notice that at least still a (modest) majority of judges does not share this approach and chooses to implement and safeguard the mandate of the European Court of Human Rights in a less minimal way, upholding a “heightened” level of freedom of expression on matters of public interest in a democratic society. The majority is of the opinion that the Swiss authorities only had a limited margin of appreciation to interfere with the applicant’s right to freedom of expression in this case, and it takes a set of criteria into consideration assessing whether Perinçek’s conviction can be considered as “necessary in a democratic society”. To that end, the majority looks at the nature of Perinçek’s statements; the context in which they were interfered with; the extent to which they affected the Armenians’ rights; the existence or lack of consensus among the High Contracting Parties on the need to resort to criminal law sanctions in respect of such statements; the existence of any international law rules bearing on this issue; the method employed by the Swiss courts to justify the applicant’s conviction; and the severity of the interference (§ 228).

The bottom line of the majority’s reasoning is that Perinçek’s statements had to be situated in a heated debate of public concern, touching upon a long standing controversy, not only in Armenia and Turkey, but also in the international arena. His statements were certainly virulent, but were not to be perceived as a form of incitement to hatred, violence or intolerance. The Grand Chamber emphasizes that it is

“aware of the immense importance attached by the Armenian community to the question whether the tragic events of 1915 and the following years are to be regarded as genocide, and of that community’s acute sensitivity to any statements bearing on that point. However, it cannot accept that the applicant’s statements at issue in this case were so wounding to the dignity of the Armenians who suffered and perished in these events and to the dignity and identity of their descendants as to require criminal law measures in Switzerland”

The judgment reiterates that statements that contest, even in virulent terms, the significance of historical events that carry a special sensitivity for a country and touch on its national identity cannot in themselves be regarded as seriously affecting their addressees (§§ 252-253).

By analysing and referring to its earlier case law, the Court clarifies that similar to the position in relation to “hate speech”, the Court’s assessment of the necessity of interferences with statements relating to historical events has been “quite case-specific and has depended on the interplay between the nature and potential effects of such statements and the context in which they were made” (§ 220). After setting out the analysis of the set of relevant criteria and case-specific elements (cfr. § 228) and after balancing the conflicting rights at issue (freedom of expression under Article 10 vs. the right of reputation and (ethnic) dignity under Article 8), the majority of the Grand Chamber reaches the conclusion that Perinçek’s right to freedom of expression has been violated by the Swiss authorities.

The Grand Chamber summarises its finding as follows:

“Taking into account all the elements analysed above – that the applicant’s statements bore on a matter of public interest and did not amount to a call for hatred or intolerance, that the context in which they were made was not marked by heightened tensions or special historical overtones in Switzerland, that the statements cannot be regarded as affecting the dignity of the members of the Armenian community to the point of requiring a criminal law response in Switzerland, that there is no international law obligation for Switzerland to criminalise such statements, that the Swiss courts appear to have censured the applicant for voicing an opinion that diverged from the established ones in Switzerland, and that the interference took the serious form of a criminal conviction – the Court concludes that it was not necessary, in a democratic society, to subject the applicant to a criminal penalty in order to protect the rights of the Armenian community at stake in the present case” (§ 280)

On these grounds 10 of the 17 judges come to the conclusion that the Swiss authorities have breached Article 10 of the Convention. The Grand Chamber rejects Perinçek’s claim in respect of non-pecuniary damages as the finding of a violation of Article 10 by the European Court was considered constituting a sufficient just satisfaction for any harm or damage suffered by him.

Brief comment

The most important message of the Grand Chamber’s judgment is that the criminalisation of the denial of genocide or other crimes against humanity “as such” cannot be justified from the perspective of Article 10 of the European Convention. The Grand Chamber emphasizes that the criminal offence of denial or gross minimization of the Holocaust is compatible with Article 10 as it should “invariably be seen as connoting an antidemocratic ideology and anti-Semitism”. The Court argues that Switzerland with its criminalisation of the denial of any genocide, especially without the requirement that it be carried out in a manner likely to incite to violence or hatred, took a position that cannot be reconciled with the standards of the right to freedom of expression as guaranteed by Article 10 ECHR and other international treaties. In this respect the Court also refers to the General Comment nr. 34 of the United Nations Human Rights Committee on Article 19 UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, stating in para. 49 that “(l)aws that penalize the expression of opinions about historical facts are incompatible with the obligations that the Covenant imposes on States parties in relation to the respect for freedom of opinion and expression. The Covenant does not permit general prohibition of expressions of an erroneous opinion or an incorrect interpretation of past events”. The Court also clarifies why Switzerland was not required under its international law obligations to criminalise genocide denial as such.

In line with the Chamber judgment, the majority of the Grand Chamber also confirms that Article 17 (abuse clause) can only be applied on an exceptional basis and in extreme cases, where it is “immediately clear” that freedom of expression is employed for ends manifestly contrary to the values of the Convention. As the decisive issue whether Perinçek had effectively sought to stir up hatred or violence and was aiming at the destruction of the rights under de Convention was not “immediately clear” and overlapped with the question whether the interference with his right to freedom of expression was necessary in a democratic society, the Grand Chamber decided that the question whether Article 17 was applicable had to be joined with the examination of the merits of the case under Article 10 of the Convention. As the Court found that there has been a breach of Article 10 of the Convention, there were no grounds to apply Article 17 of the Convention (§§ 281-282) (on art. 17’s abuse clause, see Cannie en Voorhoof).

The Grand Chamber’s judgment in the case of Perinçek v. Switzerland will certainly give cause to further analysis and controversial debate about the (desirable or necessary) limits of the right to freedom of expression in relation to genocide denial, memory laws and hate speech. With its judgment of 15 October 2015 the European Court of Human Rights has undoubtedly contributed to safeguarding the right to freedom of expression. Just one day after the closing of the Council of Europe conference questioning whether freedom of expression still is a precondition for democracy, the Grand Chamber of the Strasbourg made a robust statement that a democratic society must safeguard the right “to express opinions that diverge from those of the authorities or any sector of the population”, refusing to accept the necessity of criminal convictions for speech that does not manifestly incite to hatred, violence or discrimination and by refusing to apply the abuse clause of Article 17 of the Convention.

* Dirk Voorhoof is professor at Ghent University (Belgium) and lectures European Media Law at Copenhagen University (Denmark). He is also a Member of the Flemish Regulator for the Media and of the Human Rights Centre at Ghent University. He is the author of the recently published E-book, Freedom of Expression, the Media and Journalists: Case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, IRIS Themes, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2015, 409 p.

8 Comments

[…] post originally appeared on the Strasbourg Observers Blog and is reproduced with permission and […]

[…] as applied in its Grand Chamber judgment in Perinçek v. Switzerland (see also our blog post here). Therefore, the ECtHR examines the case with a particular regard to the context in which the […]

[…] as applied in its Grand Chamber judgment in Perinçek v. Switzerland (see also our blog post here). Therefore, the ECtHR examines the case with a particular regard to the context in which the […]

[…] Voorhoof, D. (2015, October 19). Strasbourg Observers. Retrieved from Strasbourg Observers: https://strasbourgobservers.com/2015/10/19/criminal-conviction-for-denying-the-armenian-genocide-in-… […]

[…] or debate on questions of public interest must be strictly interpreted (Gündüz v. Turkey and Perinçek v. Switzerland). It is indeed the Court’s consistent approach to require very strong reasons for justifying […]

[…] or debate on questions of public interest must be strictly interpreted (Gündüz v. Turkey and Perinçek v. Switzerland). It is indeed the Court’s consistent approach to require very strong reasons for justifying […]

[…] Court relied on Perinçek v. Switzerland (judgement – blog post) to determine if the applicant’s comments “sought to stir up hatred or violence and whether, by […]

[…] [4] Dirk Voorhoof, “Criminal conviction for denying the Armenian genocide in breach with freedom of expression, Grand Chamber confirms”, Strasbourg Observers, 19 Ekim 2015, erişim tarihi 01.10.2016, https://strasbourgobservers.com/2015/10/19/criminal-conviction-for-denying-the-armenian-genocide-in-… […]