February 07, 2020

Ingrida Milkaite is a PhD researcher in the research group Law & Technology at Ghent University, Belgium. She is working on the research project ‘A children’s rights perspective on privacy and data protection in the digital age’ (Ghent University, Special Research Fund) and is a member of the Human Rights Centre at the Faculty of Law and Criminology at Ghent University and PIXLES (Privacy, Information Exchange, Law Enforcement and Surveillance).

Two young men publicly posted a photograph of themselves kissing on Facebook. The post ‘went viral’ and attracted around 800 comments, most of which were hateful. Some of the comments featured suggestions to burn, exterminate, hang, beat, castrate, and kill the two men as well as gay people in general. The national authorities, while acknowledging that some comments were ‘unethical’, refused to launch a pre-trial investigation for incitement to hatred and violence against homosexuals. They considered that the couple’s ‘eccentric behaviour’ had been provocative and that launching an investigation in this case would be a ‘waste of time and resources’. The judgement in the case of Beizaras and Levickas v. Lithuania (Application no. 41288/15) was published on 14 January 2020. The ECtHR found a violation of Article 14 ECHR in conjunction with Article 8 ECHR, as well as a violation of Article 13 ECHR.

Facts

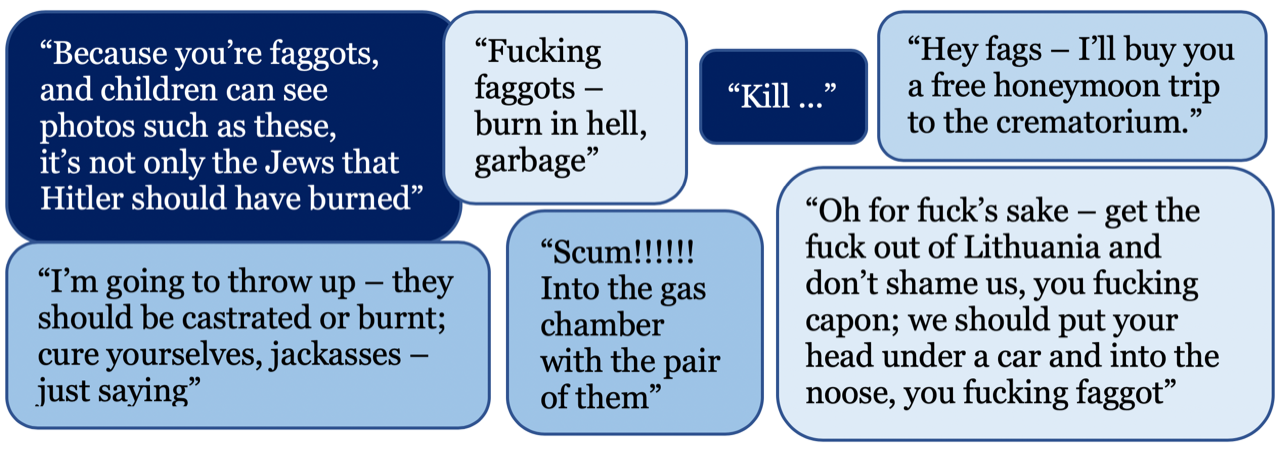

The applicants, Pijus Beizaras and Mangirdas Levickas (born in 1996 and 1995), are two Lithuanian nationals who are in a same-sex relationship. On 8 December 2014, Mr Beizaras publicly posted a photograph of them kissing on his Facebook page. By posting the picture, the applicants wished to announce the beginning of their relationship, as well as to test the level of tolerance among the Lithuanian population (§§9,91). The picture accrued some 800 comments, the majority of which were hateful. A few examples (§10):

Two days after posting the picture, the applicants asked the LGL Association (national lesbian, gay bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights association), of which they were both members, to notify the Prosecutor General’s Office of the hateful comments on the basis of domestic law (§§30,33). For the applicants, the comments were not only frightening, degrading, detrimental to their dignity and inciting discrimination, but also inciting physical violence (§16). The men decided to involve LGL and notify the authorities in its name because they feared retaliation.

However, the prosecutors refused to launch a pre-trial investigation for incitement to hatred and violence against homosexuals. The national courts unanimously confirmed this decision on all levels. The authorities decided that the comments were merely ‘unethical’, ‘improper’ and did not constitute an element of a crime. The Klaipėda City District Court considered that people posting public pictures ‘of two men kissing should and must have foreseen that such eccentric behaviour really did not contribute to the cohesion of those within society who had different views or to the promotion of tolerance’ as ‘the majority of Lithuanian society very much appreciate[d] traditional family values’ (§21). The City District Court concluded that ‘criminal proceedings were an ultima ratio measure and that they should therefore be initiated only when serious grounds and all elements of a crime existed. This was not the situation in the case at hand’ (§21). The court of final instance (Klaipėda Regional Court) endorsed these findings, also adding that by choosing to post the picture publicly (and not restrict it to Facebook friends) the applicants attempted to ‘deliberately tease or shock individuals with different views or to encourage the posting of negative comments’ (§23). This court also strengthened the arguments against the opening of the proceedings by adding that ‘it would constitute a “waste of time and resources”, or even an unlawful restriction of the rights of others [that is to say Internet commenters’]’ (§23).

Judgment of the ECtHR

The Court considered that in this situation the applicants’ homosexual orientation had indeed played a role in the way they had been treated by the authorities after they lodged the complaint. In fact, by focusing on what they considered to be the applicants’ ‘eccentric behaviour’, the criminal courts had expressly referred to their sexual orientation in their decisions (§120,121). The authorities had clearly expressed disapproval of the applicants’ public demonstration of their sexual orientation when refusing to launch a pre-trial investigation, citing the incompatibility of ‘traditional family values’ with social acceptance of homosexuality. The Court also directly stated that because of the national authorities’ discriminatory attitude, the applicants had not been protected, as was their right under criminal law, from what could only be described as undisguised calls for an attack on their physical and mental integrity. The Court thus found that the hateful comments had been inspired by a bigoted attitude (§129) towards the homosexual community in general and that ‘the very same discriminatory state of mind was at the core of the failure on the part of the relevant public authorities to discharge their positive obligation to investigate in an effective manner whether those comments regarding the applicants’ sexual orientation constituted incitement to hatred and violence, which confirmed that by downgrading the danger of such comments the authorities at least tolerated such comments’ (§129). Consequently, the Court found that the applicants had suffered discrimination on the grounds of their sexual orientation and that there had been a violation of Article 14 ECHR, taken in conjunction with Article 8 ECHR.

With regard to Article 13 ECHR, the Court found that the Lithuanian Supreme Court’s case-law as applied by the prosecutor, whose decision had then been upheld by the domestic courts, had not provided for an effective domestic remedy for homophobic discrimination complaints (§152). In particular, the Court referred to the notion of ‘eccentric behaviour’ again and noted with concern that the Supreme Court’s case-law emphasised the ‘eccentric behaviour’ of persons belonging to sexual minorities and their duty ‘to respect the views and traditions of others’ when exercising their own rights (§152). Moreover, reports by international bodies confirmed that there was growing intolerance towards sexual minorities in Lithuania (§56) and that the authorities lacked a comprehensive strategic approach to tackle racist and homophobic hate speech (§62). Consequently, the Court found that there had also been a violation of Article 13 ECHR because the applicants had been denied an effective domestic remedy for their complaints about a breach of their private life owing to discrimination on account of their sexual orientation.

Comment

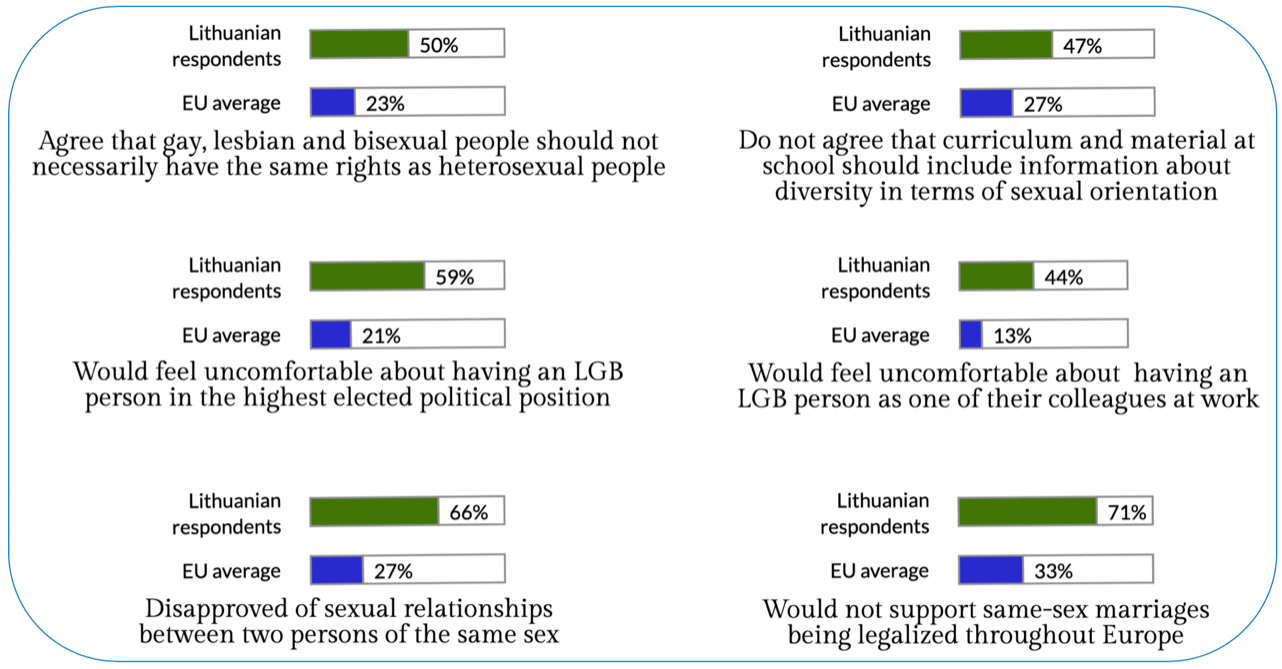

At the outset, it must be highlighted that the Lithuanian context of this case needs to be taken into consideration when discussing intolerance towards LGBT people and (online) hate speech. The Court indeed did do this and referred to international reports which shed more light on the general context in the country (§56,63,127,155). Further, as noted in the judgment (§28), the 1961 Criminal Code of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was amended in 1993 which decriminalised consensual sexual intercourse between homosexual men. Up until 1993, Article 122 of this Code provided that voluntary sexual intercourse between two men (but not women) incurred criminal liability punishable by imprisonment of up to three years. The cases where physical violence, threats, victim’s dependency or helplessness occurred, or where a child was involved, were punishable by imprisonment of between three and eight years. One of the reasons behind the change of the Code and the abolishment of this homophobic provision was, in particular, Lithuania’s (political) willingness to join the Council of Europe which required the assurance of minimal human rights standards. In that same year, 1993, the LGL – a national non-governmental organisation exclusively uniting and representing the interests of the local homosexual, bisexual and transgender community – was established and remains the only stable and mature organisation of this kind in Lithuania today. Even though a legislative change that happened some 30 years ago cannot really be called ‘recent’, some members of the Lithuanian society may still find it difficult to accept this. Indeed, fast forward approximately 25 years and we see that:

These statistics show what attitudes impact the general environment in the society and that such (majority) opinions can have a considerable effect on people’s mental health and psychological wellbeing. As rightfully stated by the third-party interveners (§5,102) and also emphasised by the Court, there is no need to demonstrate that harm had actually been caused in cases of discrimination as it was already established in the Court’s case-law (§103).

In this context it is important to draw attention to the fact that the hateful comments were indeed directed at two young adults – an 18-year-old who was a secondary school student at the time and a theology student of 19. Both men faced consequences with regard to the educational institutions they were attending. Mr Beizaras ‘had been summoned by his secondary-school headmaster, who had requested him “not to disseminate his ideas”’ (§24). Mr Levickas, for his part, ‘had been summoned by the dean of the university theology faculty, who had requested him to change his course of study because his “lifestyle did not correspond with the faculty’s values”’ (§24). In addition to verbal harassment in public places and the threatening private messages they received, these young people were not only deprived of their right to the protection of private life and their right not to be discriminated against – their rights to education, freedom of expression and association, and human dignity were also substantially affected in a negative way.

Impact on children and young people

The present case is focused on young adults and the impact that homophobia – expressed by some members of the society and through the authorities – has on them. Of course, while this was pre-determined by the scope of the complaint and the provided arguments, the Court’s elaboration on the impact of such an environment on (young, teenage and almost adult) children would have been timely and very welcome.

In the context of this judgment, references can be made to the Court’s case-law on the protection of minors against harmful content. Even though the ECtHR makes a reference to the Bayev and Others v. Russia (§67) case, it only does so with regard to the ‘growing general tendency to view relationships between same-sex couples as falling within the concept of “family life”’ (§122). The Court misses the opportunity to elaborate on the impact of such legal conceptions on children in particular which were the focus of the Bayev case. In fact, Bayev and Others v. Russia clearly established that ‘to the extent that the minors who […] were exposed to the ideas of diversity, equality and tolerance, the adoption of these views could only be conducive to social cohesion (§82). According to this case’s reasoning, children should be aware of the existence of sexual minorities. In addition, the Court also adopted a strong stance with regard to the importance of children being educated on LGBT issues:

The Court recognises that the protection of children from homophobia gives practical expression to the Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation Rec(2010)5 which encourages “safeguarding the right of children and youth to education in safe environment, free from violence, bullying, social exclusion or other forms of discriminatory and degrading treatment related to sexual orientation or gender identity” (para 31) as well as “providing objective information with respect to sexual orientation and gender identity, for instance in school curricula and educational materials” (para 32) (Bayev and Others v. Russia (§82)).

It is clear from the facts of the present case and recent events described below, that the ECtHR case law is not taken into account neither by the Lithuanian courts, nor the legislative authorities. Today, meaningful discussions on LGBT rights are crucial, especially for young people and children. Present-day children are exploring their identities, including sexual identities, in a society where hate speech against LGBT minorities is widespread and where a big part of this society not only believes that children should not be educated on LGBT issues but where LGBT family models can actually be censored. Indeed, the Lithuanian Law on the Protection of Minors against the Detrimental Effect of Public Information bans information which has a negative impact on minors, that is – public information that may be harmful to the mental or physical health, physical, mental, spiritual or moral development of minors (Article 4(1)). Article 4(2)16 of this law prohibits public information which ‘defies family values’. Such defiance includes public (1) information ‘expressing contempt for family values’, (2) information encouraging marriage and creation of a family other than between a man and a woman (as stipulated in Article 38 of the Lithuanian Constitution and the Civil Code) (§61).

This law is applied and has practical effects. For example, in 2014 a TV programme aiming to promote tolerance towards LGBT people was not broadcast because it ‘seemed to portray a same-sex family model in a positive light, which […] [was] considered to have a negative impact on minors and to be in violation of the law’ (§92). This law also resulted in an educational children’s book ‘Amber Heart’ (Gintarinė širdis) being withdrawn from the bookshops because:

The book contains fairy tales featuring members of socially vulnerable groups, such as same-sex couples, Roma, and disabled people, and aims at promoting tolerance and respect for diversity among children. [The book was described] as ‘harmful, primitive and biased homosexual propaganda’. [It was officially] concluded that two fairy tales that promote tolerance for same-sex couples are harmful to minors [… and thus] in violation of the [Law] because they encourage ‘the concept of entry into a marriage and creation of a family other than stipulated in the Constitution […].’ The experts also considered the stories to be ‘harmful, invasive, direct and manipulative’ (§61).

It is evident that such issues are still very relevant to the Lithuanian society today. In fact, this particular issue concerning the withdrawal of the book might still come back to the Court’s attention in the near future. In December 2019, the author of the book Neringa Dangvydė actually submitted her application to the ECtHR. She asks the Court to confirm that this Law is promoting censorship, that the information in the book is not harmful to minors, and that people in same-sex relationships are not inferior and should not be hidden from minors.

As these abovementioned events in Lithuania happened a while ago – in 2014 – one could think that things have changed in the meantime. However, around the same time as Ms Dangvydė’s application was submitted – at the end of 2019 – the national broadcaster LRT showed ‘Colors’ – a documentary by Elena Reimerytė portraying gay dads raising children in the United Kingdom. This broadcast led to public outrage and conservative groups demanded LRT to stop promoting ‘sexual perversions and other family concepts’. Be that as it may, the negative reactions and outcry have, also, led to a petition to end LGBT content censorship in Lithuania. This petition suggests that not everybody subscribes to the general outrage directed at LGBT people but it is also illustrative of how much further Lithuanian society needs to progress on this issue.

Conclusions

This judgement does not introduce new standards, its reasoning was quite expected and is based on longstanding case-law of the ECtHR. The Court once again stressed that arguments based on the preferences of an (intolerant) majority in a society are not sufficient and have not been sufficient for a long time already (see, for example, the cases of Vejdeland and Others V. Sweden – blogpost, Alekseyev v. Russia – blogpost, Bayev and Others v. Russia – blogpost).

The real challenge associated with this case is the provision of truly effective domestic remedies in cases of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The Convention is a constantly evolving living instrument which needs to be interpreted in the light of present-day conditions and developments in the society (§122). One way to accommodate this in more practical terms is for the national authorities in Lithuania to take on a proactive role in the contemporary society and come up with a comprehensive strategic approach which would vigorously promote pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness (§106) to curb discrimination and hate speech.

7 Comments

I hadn’t checked the case law, but I find such rulings utterly ironic for a so-called “Human Rights Court”.

When you take the shine off this, in effect the ECHR advocated the infliction of active harm, including criminal law measures (in paragraph 128), against speakers that are harmless.

I’m sure this is where people start talking about feelings or very abstract endangerment, but in any case the harm here is in no way comparable to the direct harm caused by a criminal conviction and sentence.

I also note the court insisted on there being an effect on the “applicants’ psychological well-being and dignity” (paragraph 117). Dignity is hard to measure, but psychological well-being could in theory be determined by psychological evaluation. None of this was taken but anyway the court insisted they were hurt. Uh…

In essence, these two jokers provoked an incident (as they admitted in paragraph 91), then when poked asked the State to punish those they provoked.

I can go even harder and say that not only did they use humans as “lab animals”, but after the experiment they reacted to undesirable results by trying to punish said “lab animals.” The malice is palpable, and the court in 119 was ridiculously forgiving of this unpleasant fact.

If you actively invite answers, the least you can do is to accept the answers you receive.

Further, the comments as quoted in paragraph 10 frankly do not, in the opinion of this reader, exceed the limits of what is typical of a flamethread and simply cannot be seen as some kind of incitement. You put your actions out in the open, you don’t expect everyone to be friendly.

The prosecutor’s assessment that it is unsystematic and within the expression of regular opinion is correct. The LGL has mentioned to some cases … OK, on the merits based on the extremely short presentation in the ECHR, I actually arch my eyebrow a lot more at these cases. Six months because he threw eggs? Really!

The ECHR would normally have been abhorred if comments of this degree had been used as a reason to convict say a political activist, and any comment as to the fact it meets the definitional elements of statutes would be brushed off. They will keep on insisting that even if the Criminal Law says in black and white this is prosecutable, they should combo it with the Constitution (which usually includes some kind of free speech clause) to NOT prosecute them, blah blah blah.

Personally, I find the desire of these two, and the LGL to inflict harm to be fundamentally reprehensible, the idea that their right to private life was violated after they publicized a chunk of it is frankly laughable.

The overall effect of this entire affair is to incite MY distate of LGBTs, when previously I can hardly care about them.

I think the ECHR sometimes needs to go back to basics. Defend vital areas like freedom of speech first. The right of homosexuals to deliberately provoke an incident to fire of criminal convictions on “lab animals” is not on the list.

[…] A picture of a same-sex kiss on Facebook wreaks havoc: Beizaras and Levickas v. Lithuania […]

[…] refusal to investigate homophobic comments posted on Facebook. For an analysis of the judgment, see here; for the issue of offensive comments on-line, see […]

[…] The judgement is closely related to the case of Beizaras and Levickas v. Lithuania (judgement – blog post), previously issued in January 2020, where the Court required the responding State to investigate […]

[…] our blog post: “The Court once again stressed that arguments based on the preferences of an (intolerant) […]