November 30, 2020

Donatas Murauskas, Assistant Professor at Vilnius University Law Faculty

Judges face a dilemma that is a core issue for the judiciary in a democracy: to react or not to react when confronted by media and politicians on pending cases? One option is to be explicit, take visible steps that support your unbiased approach. Another option is to maintain silence and focus on the case, with disregard to any external disturbances.

But it seems that the Strasbourg courts’ doctrine on the requirement to reply to party’s arguments that are decisive for the outcome of the case leaves no choice here. The ECtHR established this requirement under Art. 6 of the Convention in Ruiz Torija v. Spain and it has been confirmed in other cases. Technically, if a party raises its doubts about a court’s impartiality, this, being part of Art. 6 framework, implies the necessity to react – to explicitly reply to such arguments. But does it really?

In a recent case Čivinskaitė v. Lithuania the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) had front-row seats to this issue. National courts deliberated this case in the presence of external pressure that was pointed out by the applicant in her complaint. The courts decided not to explicitly react to this pressure, to stay focused on the main issue of the case and not to give any hint that they were affected by external opinions. The Court agreed with the national courts’ approach finding no violation. It appears that this finding could adjust the Court’s case-law on the requirement to reason decisions under Article 6 § 1 of the Convention.

Facts of the case

Ms Čivinskaitė was a senior prosecutor in the regional prosecutor‘s office in Lithuania. In 2009-2010 she supervised another prosecutor who carried out the investigation of a highly resonant case on alleged sexual molestation and the deaths of the suspects and the child’s father. The Prosecutor General’s Office began an inquiry into how the pre-trial investigation had been conducted in 2009. Following the disciplinary proceedings, the applicant was demoted. The high-ranking politicians, including the President, publicly criticized the pre-trial investigation. A Parliamentary committee of inquiry found that the regional prosecutor’s office had ‘obviously procrastinated’ in the pre-trial investigation and that the applicant had been one of the officials responsible. The media extensively covered the activities, citing critical politicians’ statements.

The applicant filed a complaint against the decision of the Prosecutor General’s Office to give her a disciplinary penalty. It included arguments on alleged unlawfulness of the decision, a disproportionate penalty, and the fact that the decision had been influenced by public statements made by politicians as well as by the media coverage of the case. The courts dismissed her appeals. Neither the first instance court, nor the appellate court commented on the applicant’s argument concerning the public statements made by politicians and the media coverage (§§ 60, 68).

Judgment

The Strasbourg judges indicated two cases – Sovtransavto Holding v. Ukraine and Kinský v. the Czech Republic – as ‘directly relevant to the present case’. In Sovtransavto Holding,the Ukrainian authorities intervened in the proceedings on a number of occasions. The national authority that was not a party to domestic proceedings used a special venue (protest) to object to the part of the national court’s decisions favourable to the applicant. The national court set aside that part. The ECtHR ruled that the use of this specific venue – protest – was incompatible with the principle of legal certainty. In Kinský, the issue centred on the remarks of high-level politicians against the applicant during the domestic proceedings, including statements about judges deliberating in the case. The Court concluded that national proceedings, taken as a whole, did not satisfy the requirements of a fair hearing.

With the above two cases in mind, in Ms Čivinskaitė’s application, the Strasbourg judges agreed that in a democracy, high-profile cases will inevitably attract comment by the media; however, that cannot mean that any media comment whatsoever will inevitably prejudice a defendant’s right to a fair hearing. The Court noted that in such cases it will examine whether there are sufficient safeguards to ensure that the proceedings as a whole are fair, requiring cogent evidence that the impartiality of judges are objectively justified (§ 122).

The Court provided an analysis with regard to three different sources of impact on judicial proceedings in this case: the parliamentary inquiry, the comments by politicians and the media campaign.

The parliamentary inquiry

The Court indicated that although the parliamentary commission expressed that the applicant’s prosecutors office had ‘obviously procrastinated’ in the pre-trial investigation and that she had been one of the officers responsible for the inaction, the conclusion of the parliamentary commission had been based on the Prosecutor’s General finding in disciplinary proceedings against the applicant.

The politicians comment

The Court considered statements made by the President, the Chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Legal Affairs, and some Members of Parliament in the national press. The most problematic statement, from a judicial independence point of view, was made by the President soon after the Prosecutor General’s Office concluded its disciplinary inquiry and recommended demoting the applicant. Here, the President gave a statement to a news website admitting that she had expected the prosecutors to receive harsher penalties.

An interesting argument made by the Court was that this comment did not affect the independence of the domestic courts as they did not give harsher penalties than the Prosecutor’s General office (i) and the domestic courts’ reasoning included a discussion on the reasonableness of the penalty (ii).

In the light of the right to a fair trial framework such arguments seem to be problematic as they do not address the actual issue – whether the comments affected the domestic courts or not. It gives a suspicion that had the domestic courts decided that the applicant should be given a harsher penalty, this would be acknowledged as a violation of Article 6 ECHR. But what if the circumstances are sufficient to give harsher penalties? Should the domestic courts disregard those circumstances so as to not risk their unbiased image?

The media campaign

The Court noted that a virulent media campaign can adversely affect the fairness of court proceedings and engage the State’s responsibility. The Court was ‘unable to accept that the language used in the media reports with regard to the applicant while the court proceedings against her were ongoing was such as to create the perception of her responsibility for any specific offences’ (§ 139).

The Court did not find violation of Article 6 of the Convention in the Čivinskaitė case. It ruled that there were no grounds to suggest that the fairness of the proceedings before the administrative courts were compromised.

The legal framework – to react or not to react?

The major challenge for the Court’s case-law is given in § 143 on the legal reasoning of the national courts’ decisions. The Court concluded that the domestic courts had answered the ‘main arguments, namely that [the applicant]… had acted in accordance with the relevant legal instruments and that the penalty given to her had been disproportionate’. The Court then dealt with the national courts’ silence with regard to possible bias alleged by the applicant:

‘In view of the rather general way in which the applicant formulated her complaint concerning the fairness of the proceedings…, as well as the detailed reasons given by the courts to justify the decision to give her a disciplinary penalty…, the Court is prepared to accept that their silence on this issue can reasonably be construed as an implied rejection’.

The domestic courts’ silence was justified by two arguments, the first being that the applicant’s complaint was formulated in a ‘rather general way’, and the second being that the domestic courts provided a detailed reasoning on the reasonableness of her disciplinary penalty.

As for the first argument, in the descriptive part of the judgment the Strasbourg judges summarised the applicant’s complaint to the first instance Vilnius Regional Administrative Court in the following way:

‘the applicant submitted a revised complaint in which she additionally argued that the decision to demote her had not been based on her performance but that it had been influenced by public statements made by politicians, who had insisted on strict punishments for investigating officers, as well as by the media coverage of the case – she referred to the publications quoted in paragraphs 39, 40 and 45 above’ (§ 52).

If such information was indeed in the complaint, it is rather difficult to understand how the Court was able to conclude that the complaint was formulated in a ‘rather general way’.

The second argument is extensively analysed in the dissenting opinion of Judge Bošnjak. He points out that:

‘the argument of the majority that the omission of the Lithuanian administrative courts did not render the proceedings as a whole unfair…is…inconsistent with the well-established approach of the Court. Notably, a single failure to comply with the obligation of domestic courts to provide reasons for dismissing a relevant submission of a party has sufficed for the Court to find a violation of Article 6 § 1 of the Convention’.

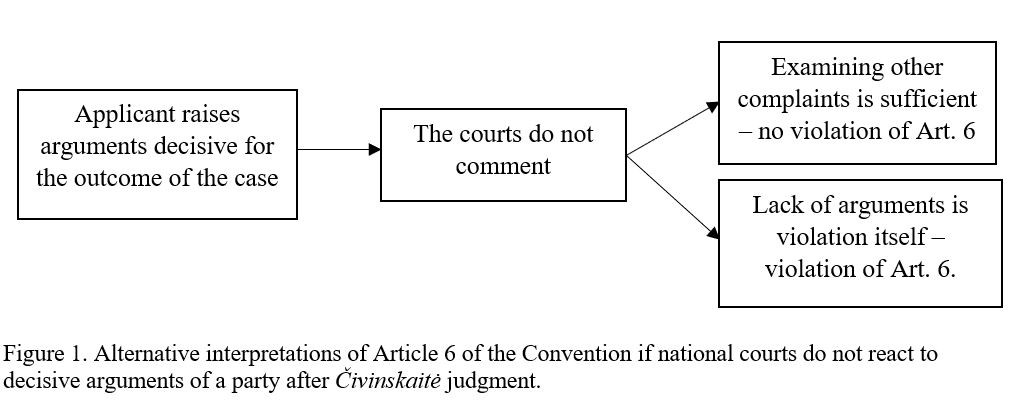

It appears that by accepting the national courts (lack of) reasoning, the Court compromised on its own ‘obligation to reason’ doctrine under Article 6 of the Convention. Instead, the Strasbourg judges suggest an alternative way to apply the fair trial clause if the applicant raises arguments decisive for the outcome of the case. I summarise the two approaches below.

The outcome in Čivinskaitė case resonates with another line of ECtHR cases on the obligation of national courts to reason why they did not refer the case to the Court of Justice of the EU for a preliminary ruling. In his blogpost Jasper Krommendijk indicates that this case law is ‘highly dependent upon individual judges involved’. Some judges apply a more intensive test, requiring extensive reasoning of the national court if it decides not to apply to the Court of Justice of the EU – one of examples is Baltic Master case. Other judges are more pragmatic, arguing that the seriousness of the infringement should be considered – for example, the Baydar judgment.

It seems that the Čivinskaitė case echoes this fragmentation of the case law between more liberal and more pragmatic approaches – in this case the Court was more pragmatic. In the Čivinskaitė case the Court decided to consider the ‘main’ issue of the domestic case. Whereas, in the Baltic Master case the Court ruled that Lithuanian courts violated Article 6 ECHR due to insufficient reasoning not to refer the case to the Court of Justice of the EU, disregarding the ‘main’ case.

Conclusion

Reading the actual decisions of the Vilnius Regional Administrative Court and the Supreme Administrative Court of Lithuania I have no reason to doubt their reasonableness. And I do not think that answering the question on the need to react to existing pressures is easy. But I doubt whether it fits the doctrine of the Court – the obligation to reason the rejection of any decisive arguments submitted by parties. It seems that the judicial deliberation at the national courts could have been emphasized much more from this standpoint. For example, the Court could have had put more weight on the relevant management of cases conducted by courts such as the composition of a three judge panel instead of a one judge in the Vilnius Regional Administrative Court.

In a seminal book ‘The Judge in a Democracy’ Aharon Barak expressed the idea that the tension between the courts and other branches of law ‘is natural and…also desirable’, acknowledging that sometimes the criticism towards the courts transforms into ‘an unbridled attack’. He suggests that judges do not have much choice in tension between courts and other branches – ‘[t]hey must remain faithful to their judicial approach; they should realize their outlook on the judicial role’ (p. 216).

Perhaps, he is right and there is not so much courts can do except to focus on the deliberation of their cases. Yet, it is not clear from the case law of the Strasbourg court, and I very much join Jasper Krommendijk in waiting for the Court to clarify the ‘obligation to reason’ standard.