May 14, 2021

Francesco Luigi Gatta, Research Fellow, UCLouvain, EDEM

Thursday 13 May 2021 is a holiday in France, celebrating the Ascension. As a consequence, various offices and services are closed. The European Court of Human Rights makes no exception in this respect. The Court is also remaining closed for the following day, Friday 14 May.

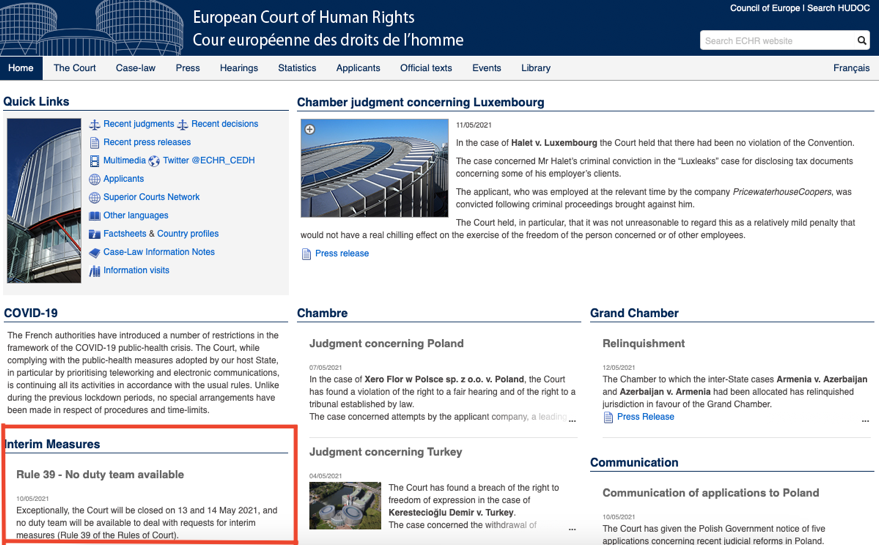

Nothing strange, so far. Until Monday, 10 May, when this announcement was published in the home page of the Court’s website:

Such a statement is particularly worrying.

In short, this would mean that the Court remains closed for two days, during which, ‘exceptionally’, there will be no reception nor processing of Rule 39 requests for interim measures. A ‘blackout’ that is quite serious, alarming and hardly explainable.

Rule 39 of the Rules of the Court allows applicants to request and obtain interim measures in case of an imminent risk of irreparable damage. The Court may indicate those measures to the State concerned, which will be required to do something or to refrain from doing something with regard to the individual situation of the applicant. Interim measures are binding upon the States.

That is, in other words, an ad hoc system of human rights protection designed for emergency situations. In many cases, indeed, Rule 39 may represent a crucial tool to safeguard, not only the human rights of a person, but to actually save their life.

The vast majority of interim measures concern deportation and extradition cases, where the Court may require the State concerned to suspend a deportation order against an alien, thereby preventing potential violations of Articles 2 or 3 of the Convention. Rule 39 has been triggered also in cases of nutrition, hydration or artificial ventilation of individuals (e.g. Lambert and Others v. France; Gard and Others v. the United Kingdom). Most recently, in February 2021, interim measures had been granted in the case of the Russian opposition leader Aleksey Navalnyy, with the Court ordering Russia to release him from detention. Rule 39 has also been invoked and applied in inter-State cases, including the recent armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. When it comes to inter-State disputes, however, the effectiveness of interim measures is debated and has been questioned (for the interim measures in the framework of the conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh and a sceptical opinion in this respect, see here; for a different position, see here).

Regardless of the alleged lack of effectiveness of interim measures in those cases, inter-State disputes only represents a small portion of the litigation in Strasbourg (around 30 applications since the Court was created, although the number is on the rise. For the full list of inter-State cases, see here). It is in individual cases that interim measures have proven to be a relevant tool for protection, often with a decisive impact on the rights and safety of the applicant. Despite the potential crucial role played by interim measures, the Duty team of the Court dealing with Rule 39 requests will not be operative during 13 and 14 May. This triggers some considerations.

First, to the best of my knowledge, Rule 39 requests have always been received and processed by the Court, including during the holidays. Not even the Covid-19 pandemic, with the disruptive force of its ‘first wave’, was able to stop the Court from dealing with requests for interim measures under Rule 39 (see the press releases of 16 March 2020, where, despite the lockdown measures introduced by the French government, the Court ensured ‘the examination of urgent requests for interim measures under Rule 39 of the Rules of Court’. Similarly, see the press releases of 27 March and 9 April 2020).

Second, the two-day ‘hole of protection’ was announced on the Court’s website on 10 May 2021, that is, three days in advance. What if a government, taking good note of such window, has organised and implemented a number of ad hoc expulsions or extraditions of personae non gratae? A potential good opportunity in this respect, knowing that there will be no immediate consequences in Strasbourg.

Third, the disruption of this essential service by the Court is not explained. Only a laconic statement provided on a website, informing that ‘exceptionally’ (‘à titre exceptionnel’, in the French version) the ad hoc team dealing with Rule 39 requests will not be operating for two days. No further details, no explanation. This is quite surprising considering the transparency policy the Court is recently pursuing (explaining, for example, its new case-processing strategy, the priority policy, and also resorting, for this purpose, to Q&As, summary documents, etc.). So why does the Court fall short here? This is even more inexplicable considering what is at stake. Imagine someone who, being badly injured and in urgent need for medical treatment, runs to the emergency room of the hospital, but finds this communication: sorry, no first aid today, we are closed.

Such a serious hole of protection in the Court’s system would have needed at least an explanation. What are the exceptional reasons that in these two days have disrupted such an important service like the processing of interim measures? One truly hopes that this is not because of the holidays.