October 18, 2022

In September 2022, the European Court of Human Rights handed down its decision in Thevenon v France, rejecting as inadmissible a challenge to the workplace vaccination requirements enforced following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in France.

That such an application would be declared inadmissible is not at all novel and represents something of a standard response by the court to challenges against measures adopted by states in response to the Covid-19 pandemic so far. Now that almost two years have passed since the court handed down its first decision relating to such a case, there is now a sufficient corpus of decisions and judgments from which we can assess the court’s ‘covid case law’ as a whole.

This post will reflect on this body of case law, and considers how the court has handled applications, which kinds of claims have been successful, and how the court might usefully develop ‘covid case law’ in the future.

By ‘covid case law’ I am talking about two broad kinds of cases. Firstly, there are challenges brought against states relating to measures adopted in order to limit the spread of the virus; the claim in these cases is (usually) one relating to negative obligations: the state has acted in breach of the Convention by ushering in measures which breach human rights. Such challenges can be further distinguished according to whether they are aimed at the act of closing off public spaces, such as schools and religious buildings (or in the case of the harshest lockdowns, spaces outside the home altogether) and those aimed at the conditions placed upon accessing those spaces, such as being required to wear a mask, take a vaccine, or show proof of a negative test in order to participate fully in society.

Secondly, there are cases brought against states for a failure to act during various points in the pandemic in order to reduce both the spread of the virus and mitigate its impacts on other aspects of life; the claim in these cases is (usually) related to positive obligations: the state has failed to secure to its citizens the rights under the Convention. Again, here it is useful to distinguish general inaction claims, aimed at states for failing to reduce the spread of the pandemic generally, and those which relate to the pandemic’s impact on specific institutions such as courts and prisons.

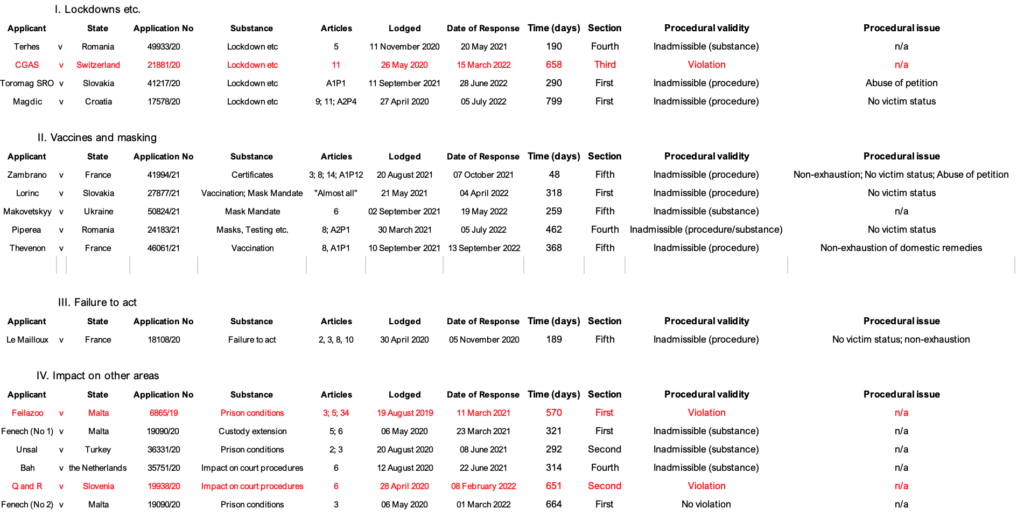

Some basic information about many of the cases discussed below are presented in the following table. This allows for a birds-eye view of the major trends in the court’s ‘covid case law’. The few cases in which a violation was found by the court are highlighted in red.

As can be seen in the table above, the court has been unusually keen to dismiss applications for procedural reasons: for example, the Court declared the application in Magdic v Croatia to be manifestly ill-founded on the basis that the applicant did not provide specific information about how they were personally impacted by the lockdown measures; they could not, as such, be considered victims for the purposes of the Convention, and the Court would not countenance what it considered to be an actio popularis because “the Convention does not… permit individuals to complain about a provision of national law simply because they consider, without having been directly affected by it, that it may contravene the Convention”. Whilst this may seem fair in relation to certain claims (for example, one aspect of the challenge involved a claim that the applicant’s religious freedoms had been infringed, without supporting information explaining why), it is difficult to see why such measures would not, intrinsically and automatically, affect the freedom of movement of the claimant.

However, not all cases were thrown out for procedural reasons. In Terhes v Romania the court ruled that a challenge to Romania’s lockdown measures, lodged under Article 5 of the Convention, was inadmissible. In brief, the court considered that, owing to the exceptional circumstances in play, the lockdown in that case did not even engage Article 5, and that the enforced stay at home orders and ban on public outings did not, apparently, deprive anyone of their liberty in the first place. Alan Greene’s excellent post, which is well worth reading, outlines the decision and its flaws at greater length; I entirely agree with his analysis.

The case of CGAS v Switzerland stands in stark contrast to Terhes, and indeed with most other cases. A fuller explanation and examination of the case is provided by Stijn Smet here, but in brief: the applicant alleged that Switzerland’s blanket ban on public demonstrations during the first months following the outbreak of the virus disproportionately infringed their right to freedom of assembly. Rather than finding the complaint inadmissible (the claimant organisation had been refused permission to organize a public gathering May 2020 and thus constituted a ‘victim’ for the purposes of the Convention), the court found not only that Article 11 was engaged, but that it was breached. Whilst the ban on public demonstrations was considered to have pursued a legitimate aim (the reduction of the spread of the virus), its severe and blanket nature was, apparently, enough to render its effect disproportionate in the circumstances.

As can be seen in the chart above, the CGAS case provides the only instance where the court has found that a lockdown measure has breached the Convention. In fact, as will be shown below, it is the only case where the court has found that the effect of any Covid-related measure, on its own, breached the Convention in any form. Perhaps because the case is such an outlier, the Swiss authorities appealed to the Grand Chamber. Its petition was accepted in September 2022; a hearing has been set for March 2023. The outcome of the CGAS case is therefore not final and binding.

The second group of cases concerns challenges to rules relating to vaccinations, the wearing of masks, and testing. The court has so far found all of these cases to be inadmissible. Often this is for procedural reasons, some of which are convincing (for example, a failure to exhaust domestic remedies in Thevenon v France), others less so (for example, a lack of a clear victim in Lorinc v Slovakia). In Piperea v Romania, the court provided a number of reasons for dismissing an application against a host of rules affecting the applicant’s job at a university, including social distancing and masking; this was partly for procedural reasons (he had not provided sufficient evidence of the effect the measures had on his life) and partly for substantive reasons (the measures were “imposed… following a state of emergency” arising in an “unforeseeable and exceptional context”, and as such did “not reveal any appearance of violation of the rights and freedoms enshrined in the Convention”). The reasoning was very brief but there is every indication that the court was prepared to dismiss the substance of the claim outright.

The case of Makovetskyy v Ukraine was also considered manifestly ill-founded. In that case, the claimant challenged the fine he was issued for failing to wear a mask in a supermarket. The lawfulness of that measure had already been challenged, and rejected, in domestic proceedings; the Strasbourg court saw no reason to upset that finding.

Taken together, we see that the court has consistently rejected challenges to the imposition of mandatory requirements, adopted by states in order stem the flow of the pandemic, at the admissibility stage.

Perhaps surprisingly, despite attracting significant academic comment at the outset of the pandemic, there are currently very few decided cases which concern complaints that states had not done enough to prevent the spread of the virus, and reduce the severity of its impact (both in terms of death, disease and disability, but also its impact on the economy, the predictable closure of schools and places of worship, etc). The main case in this category is Le Mailloux v France.

The claimant in that case complained that the French authorities had not done enough to prevent the spread of Covid (both in relation to the general public at large, as well as in some more specific situations, such as failing to provide doctors with proper equipment), and that those measures which were adopted were put in place at too late a stage to effectively reduce the spread of the virus. That case, like many others, was declared inadmissible. This finding, in retrospect, was fairly strict: the claimant had not provided sufficient information about how the pandemic had affected him (although he had complained specifically that he had caught the virus and this had seriously affected his health); neither had he sufficiently aired his complaints before domestic authorities (he had intervened in a domestic challenge, rather than bringing one of his own relating to his specific case).

The case was handed down in November 2020. As far as I can see, there have been no further challenges to a general failure to put in place preventative measures in light of the outbreak of the pandemic.

There are a lot more cases which relate to the impact of the pandemic on other state institutions, often involving claims that the state has failed to take steps to mitigate the effect of Covid on a particular service, or that the measures adopted have been inadequate. It is hard to determine exactly what constitutes a ‘covid case’ in this respect, but the cases listed in this section include a specific and concrete complaint that the pandemic, or the state’s response to it, was central to an alleged violation.

For example, a number of cases relate to prison conditions, and particularly in relation to the increased risk posed by close contact with others, something very common in prison cells across Europe. Unlike the above cases, no case of this kind has – so far – been dismissed on procedural grounds. One was declared inadmissible on the merits of the claim (Unsal v Turkey) whilst two cases involving Malta were declared admissible: one resulted in the finding of a violation (Feilazoo v Malta) and the other did not (Fenech v Malta (No 2)).

It is worth noting, however, that the Feilazoo case was not solely concerned with the prison conditions in place during the pandemic. The applicant complained of the wider conditions of his (lengthy) immigration detention; the court highlighted, amongst other factors, the fact that he was kept in a cell without proper access to natural light and ventilation, that he was not permitted sufficient exercise and that he was moved to an isolated cell as evidence that his treatment constituted a breach of Article 3 ECHR. The impact of Covid certainly made matters worse – he was placed in a cell alongside those with Covid exposure – but as Aristi Volou has pointed out, the court was not at all clear about how much weight it gave to this factor, nor did it clarify whether there were any circumstances under which exposure to a higher risk of Covid, considered alone, would raise issues for Article 3.

Other cases involve challenges to the operation of the legal system. In Bah v the Netherlands, the court rejected a challenge to the compatibility of modifications to court hearings adopted in the early stages of the pandemic, where most cases would proceed via video link and phone rather than being heard in-person. The claim under Article 6 was rejected as inadmissible: the claimant’s hearing had been fair. In Fenech v Malta (No 1), the court likewise declared inadmissible a challenge to the extension of custody detention during the early stages of the pandemic, finding it necessary in the circumstances.

A rare finding of a violation (in this case, of Article 6) occurred in Q and R v Slovenia; the court found that the consideration of the applicant’s adoption request had been excessively lengthy. The court found that whilst delays to the consideration of such applications would be inevitable in light of the pandemic, this did not justify leaving the applicant waiting for some six years for a response. In this case, Covid had severely affected the length of the delay, and it is unlikely that, but for the pandemic, the delay would have been quite so severe. At the same time, this is another example of a finding of a breach where Covid had the effect of exacerbating an existing problem, rather than creating one of its own.

Thus, it seems like the court appears to be somewhat more open to considering potential breaches which are made worse by Covid-19, rather than more direct questions relating to whether a breach arises out of the state’s response to Covid-19 itself.

In its decided cases so far, the court has been relatively reluctant to even consider a lot of challenges to state action in response to the pandemic. The court has rejected the substance of a majority of complaints relating to the state’s inaction to combat the spread of the virus, and in relation to the effects of the pandemic on the justice system. Interestingly, in a majority of cases involving more general challenges to measures, such as lockdowns and masking requirements, the court has been quick to discard cases altogether, often on procedural grounds.

As has been shown, the CGAS case is the only case against lockdown measures (so far) to result in a finding of a violation (and that is being reviewed by the Grand Chamber shortly). Whilst the impact of the pandemic contributed to a finding of a violation in both Feilazoo and Q and R, the pandemic can at best be considered an aggravating factor in the wider factual matrix, rather than the sole, or main, cause of the violation itself. The correctness of CGAS is also in doubt, being due before the Grand Chamber for re-assessment in due course.

In one sense, it is understandable why the court has been reluctant to deal with many challenges via a full and reasoned judgment. Most interferences complained of are relatively minor, whereas the gravity of the reasons behind the measures adopted is significant. The weight of the margin of appreciation afforded to states in this context is significant, and rightly so.

At the same time, there are dangers to this approach. Some of the arguments presented by the court feel unreal. It is hard to believe, for example, that lockdowns do not constitute a deprivation of liberty (whether they can be justified is a trickier question: see paragraph 18 of the case of Hotta, handed down by the Administrative Court of England and Wales; my own view is that the architecture of Article 5 is more rigid than this passage suggests, for reasons broadly set out by Greene here). Further, the court could reduce its future workload, and provide some reassurance to domestic courts, if it dealt with one of the challenges to the imposition of measures mitigating the impact of the pandemic via a full and reasoned judgment. There would be great benefit were the court to put the Convention-compatibility of state measures requiring citizens to comply with inconvenient, but important rules such as having to wear a mask on public transport in order to prevent the spread of a deadly disease beyond any doubt.

1 Comment

Excellent overview, Lewis! Many thanks for providing it. I agree re. the interpretation of “deprivation of liberty” in art. 5, in particular. As in Austin v UK, the less-than-convincing interpretation could be explained, in line with your view of the architecture of art. 5 ECHR (which I share), by the fact that a finding of deprivation of liberty might inevitably lead to a finding of a violation of art. 5 ECHR. Avoiding such a finding necessitates (it seems) somewhat contorted interpretation of the concept “deprivation”. Other than that, I wonder if the GC will be likely to provide more, rather than less, guidance in CGAS. Less guidance seems the more likely course of action for a Court that on the whole prefers to leave these matters to the national authorities.

1 Trackback