October 20, 2023

by Harriet Ní Chinnéide

This September, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR, the Court) delivered four rulings in cases involving the expulsion of settled migrants from Denmark. In two of them, the Court found in favour of the State and in the other two, it found a violation of Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life) of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR, the Convention). In all of these rulings, the Court assessed the balance to be struck between competing interests in accordance with established criteria and in all of them, it reiterated its well-rehearsed refrain: where domestic authorities have carefully considered the case in line with the criteria set out in the Court’s case law, strong reasons are required for the Court to substitute its assessment for theirs.

This post situates the ‘September cases’ within the Court’s broader jurisprudence on expulsion under Article 8. These decisions provide further illustration of the Court’s typically procedural and subsidiary focused approach in this area – while simultaneously demonstrating the limits of the Court’s willingness to defer to the decisions of domestic authorities when it fundamentally disagrees with them on a substantive level. Although the Court didn’t point to any procedural failings on the part of Danish authorities in any of these cases, in two of them it succeeded in finding the requisite ‘strong reasons’ to substitute its own assessment for that of the Danish courts. What were they and how did they allow the Court to overturn domestic decisions?

Both applicants entered Denmark as young children. They were both convicted of numerous criminal offences and issued with an expulsion order and a 12-year re-entry ban.

As a minor, Mr Noorzae was convicted of several criminal offences, receiving short suspended sentences. As an adult, he was fined several times for theft and vandalism. He was sentenced to 1 year and two months imprisonment and cautioned about the risk of expulsion after being convicted of possession of cannabis intended for distribution, violence against two individuals, possession of a knife and driving without a licence. He appealed to the High Court but was unsuccessful – instead, it convicted him of an additional count of attempted threats, increased his sentence to one year and three months imprisonment and issued him with an expulsion order and a 12-year re-entry ban. This was despite his arguments that he had undergone therapy and resumed his studies. Mr Sharifi had a similar criminal record, committing several offences as a minor. In addition, as an adult, he was found guilty of repeated violence, violating the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), possession of two shotguns in a public place, with a view to their illegal sale and possession of .4 grams of cocaine. He was sentenced to two years and 6 months imprisonment an expulsion order with a 12-year re-entry ban was issued against him by the District Court. It was upheld on appeal by the High Court despite the fact that his girlfriend was now pregnant with their child, conceived while he was in pre-trial detention.

In assessing the proportionality of the measures ordered against the applicants, the Court first acknowledged that the Danish courts “took as their legal starting-point the relevant sections of the Aliens Act, the Penal Code and the criteria to be applied in the proportionality assessment, by virtue of Article 8 of the Convention and the Court’s case-law.” (para 25, both judgments) Although the Court accepted that the domestic courts had thoroughly examined the relevant criteria, it found that it was called upon to examine whether the domestic courts had adduced and examined “very serious reasons” to justify the expulsion of applicants. In both cases, it found that the domestic courts had not done so and that the measures were disproportionate to the aims pursued and violated Article 8. In the case of Mr Noorzae the Court highlighted that he had a lack of relevant prior convictions, had been given a lenient sentence and had not been warned about the risk of expulsion, had made efforts to reintegrate into Danish society after serving his sentence and had very strong ties with Denmark and virtually non-existent links with Denmark. Similarly, Mr Sharifi also lacked relevant recent prior convictions, had had a relatively lenient sentence imposed against him and had not been warned about his possible expulsion. He too had strong ties with Denmark and negligible ties with his country of origin. Further, the possibility of a more lenient sentence had not been explored.

Like the applicants in the previous cases, both Mr Goma and Mr Al-Masudi entered Denmark at a young age. They were both convicted of numerous criminal offences and issued with expulsion orders and a permanent ban on re-entry. In contrast to the previous cases, they had both been issued with a prior suspended expulsion order and warned about possible expulsion. In both cases, the Court found that no violation had occurred and that the proportionality of the interference had been duly assessed by domestic courts in light of the Court’s case-law. In addition, both Mr Goma and Mr Al-Masudi had been convicted of more serious offences. Mr Goma was found guilty of rape as an adult and Mr Al-Masudi was convicted of multiple drugs offences, aggravated violence and assault and keeping a sawn-off shotgun and spare cartridges in an unlocked cabinet in his living room in particularly aggravating circumstances.

The Court approached these cases in the same way as it did the previous ones. Here, however, it endorsed domestic courts’ conclusions. It held that the interference with Article 8 was supported by relevant and sufficient reasons and that national authorities had adequately adduced ‘very serious reasons’ justifying the measures against the applicants. At all levels of jurisdiction, there was an explicit and thorough assessment of whether the expulsion order could be considered contrary to Denmark’s international obligations. In this regard, the Court pointed out that ‘where independent and impartial domestic courts have carefully examined the facts, applying the relevant human rights standards consistently with the Convention and its case-law, and adequately weighed up the applicant’s interests against the more general public interest in the case, it is not for the Court to substitute its own assessment of the merits (including, in particular, its own assessment of the factual details of proportionality) for that of the competent national authorities.’ (para 25 in both rulings) This will only be the case where there are strong reasons for the Court to do so.

No such strong reasons were found in these cases and thus Article 8 was not violated.

Despite being the first country to ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention, Denmark has now developed an ‘ultra-conservative’ migration policy. Initially implemented by the right for almost 20 years, since 2019 it has been continued by the Social Democrats who adopted a restrictive approach to immigration following their defeat in the 2015 election. This volte-face enabled them to win back the confidence of many voters who had shifted their support to the populist right and contributed to their victory in the 2019 elections. Today, the country is governed by a bipartisan coalition, which bridges the left-right divide, and restrictive migration policies have become the baseline in Danish politics. In light of Denmark’s hardline stance on migration, it is perhaps unsurprising that cases against the State make up a significant proportion of the Court’s jurisprudence on expulsion under Article 8. In the discussion that follows, I will first provide some further details on the Court’s case-law in this area. I will then focus more directly on the Court’s September rulings and the approach adopted therein

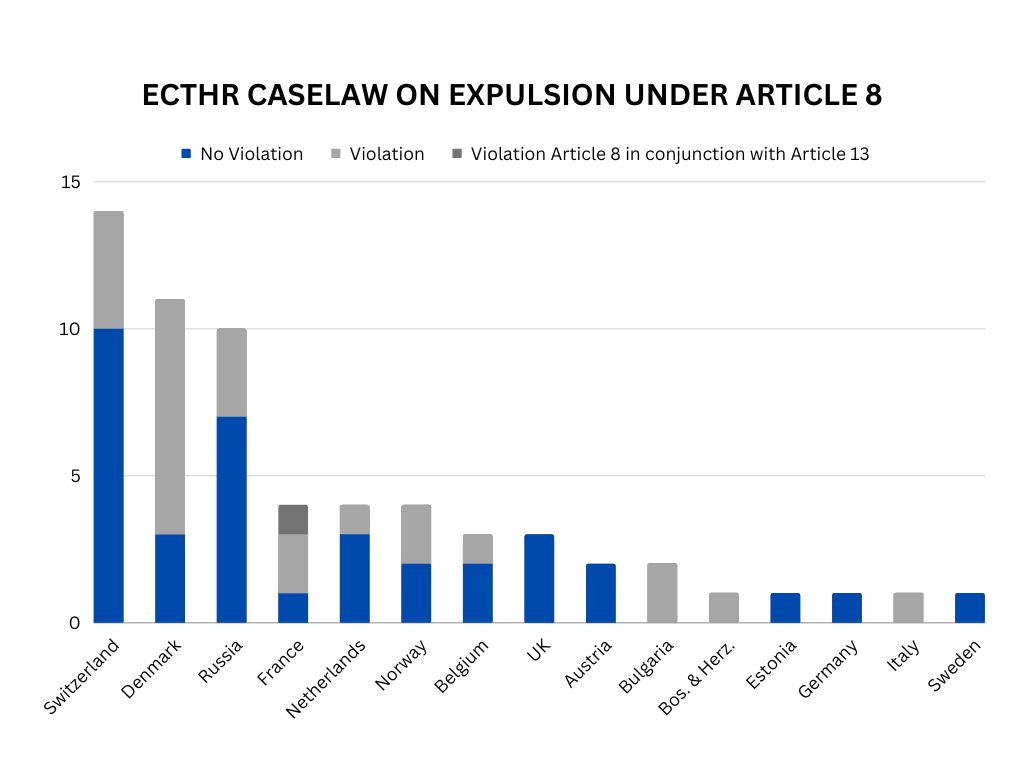

A search on the HUDOC database reveals that the ECtHR has issued 63 judgments on the merits in cases concerning expulsion under Article 8. [1] Fourteen of the cases identified were against Switzerland, eleven against Denmark and ten against Russia. The overall distribution of cases can be depicted as follows:

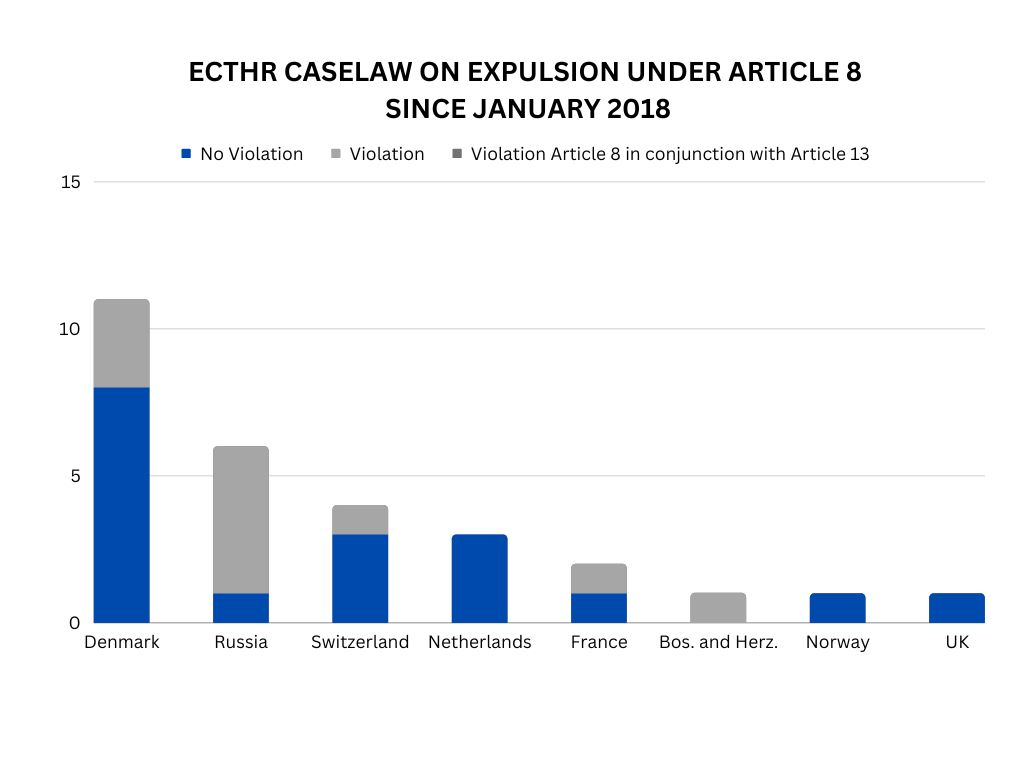

From this table we can see that the majority of cases in this area result in a finding of no violation and that only Switzerland has been involved in more cases than Denmark. On this, is it also interesting to observe that all eleven cases against Denmark were adjudicated since 2018. Thus, if we look at the data from the last six years we can see that it has surged ahead to occupy the lead position, well ahead of Switzerland and Russia (which has since left the Convention system). Of all eleven cases against Denmark, only three led to a finding of a violation – two of these were issued this September and the third, Abdi v Denmark, was delivered in September 2021. All three of these cases related to the expulsion of settled migrants. The distribution of cases since 2018 can be seen in the figure below.

In earlier posts on this blog (see here and here), I have written about the Court’s deferential approach in cases concerning the expulsion of settled migrants. This approach can be traced back to a broader ‘procedural turn’ detected in the Court’s jurisprudence which is closely linked with the principle of subsidiarity and the margin of appreciation doctrine. When the Court adopts a procedural approach in cases involving competing rights and interests, its review focuses on the quality of the balancing exercise conducted at the domestic level rather than on the outcome thereof. Provided domestic authorities properly engage with the requirements set out in the ECHR and review the case in accordance with the criteria set out in Court’s jurisprudence, it will display a willingness to defer to their decisions. In other words, if the domestic review is adequate from a procedural perspective, strong reasons are required for the Court to substitute its own substantive assessment of the case for that of the national courts. This was reiterated by the Court in all four of the judgments under discussion.

In the context of expulsion, the ECtHR has developed very clear criteria to be considered by domestic authorities when striking a balance between the rights of the applicant and the general interests of society. These criteria were clearly defined by the Grand Chamber in Üner v the Netherlands. Among other factors, they include the nature and seriousness of the offence(s) committed by the applicant; the length of the applicant’s stay in the host country; the best interests and well-being of any children involved and the solidity of the applicant’s social, cultural and family ties with the host country and with the country of destination. For a full list of the criteria see paras 57-58 of the Üner judgment.

Arguably, the Üner criteria bring a welcome degree of clarity and predictability into this area of the Court’s jurisprudence. They recognise the importance of protecting the best interests of children and require authorities to undertake a comprehensive review of each individual situation. Furthermore, the criteria have the potential to effectively encourage more active engagement with ECHR requirements at the national level. They send an explicit message to domestic authorities about what factors they need to take into account if they want to benefit from more lenient review at the European level. On the other hand, however, there is also a risk that this style of review can cause the Court to develop a ‘check-box’ approach to rights protection. The plight of the individual applicant may be overlooked, as substantive human rights violations perpetrated against them are concealed beneath a veneer of procedural propriety. Arguably, the Court’s finding of a violation in Sharifi v Denmark and Noorzae v Denmark speaks against this fear to some extent as the Court demonstrated its continued ability to conduct its own substantive assessment of the proportionality of an impugned measure when required – even in an area where deferential, procedural review has become its default approach. (Although it can still be asked whether strong reasons to overrule domestic decisions should have been found in other cases too.)

In all but one of the Court’s previous judgments involving cases against Denmark, the Court accepted both the quality and outcome of the domestic authorities’ proportionality assessment. What made Sharifi and Noorzae different? When we compare the rulings delivered in September, the severity of the crimes committed by the applicants, the first of the Üner criteria, emerges as a distinguishing factor between the cases where a violation was found and those where it was not. However, of equal significance seems to have been the fact that both Mr Gomez and Mr Al-Masudi had been given a fair warning that there was a real possibility of their expulsion: both men had been issued with a suspended expulsion order with a two-year probation period, both of them had been convicted of further criminal offences during this time. This had not been the case for Mr Sharifi or Mr Noorzae – and nor had it been for Mr Abdi, the applicant in the only other case where a violation against Denmark was found. It would be an oversimplification to suggest that these were the only two differences between the applicants’ various individual situations but what these rulings do show is that although a “warning” requirement is not listed among the Üner criteria, it can carry significant weight in the Court’s assessment.

Returning to the Üner criteria, it is also interesting to observe that in its judgment in Al-Masudi, the ECtHR did not refer to the best interests of the applicant’s child. The child was conceived while Mr Al-Masudi was in pre-trial detention and he had never lived with his girlfriend nor the child. The Court found that Mr Al-Masudi’s expulsion would interfere with his private life but not with the family life he had begun with his girlfriend while both of them knew that he had a ‘precarious immigration status.’ (para 32) In such a situation, it would only be in exceptional circumstances that the removal of the non-national parent would constitute a violation of Article 8. While this is in accordance with previous case-law (see for example, Jeunesse v the Netherlands), it seems a bit artificial to argue that the parents’ prior knowledge of the precariousness of one of their immigration statuses says anything about what would be in the best interests of the child. Although a more direct consideration of the ‘best interests’ criterion may not have led to a different outcome in this case, the Court can be criticised for its failure to consider this element – and indeed, for its failure to examine how it was considered at the domestic level. This brings me back to an argument I already made in an earlier post on Otite v the United Kingdom. While it is certainly a positive development to see the Court finding a violation of Article 8 in cases where it deems that it has sufficiently strong reasons to find the domestic court’s decision disproportionate, this is not enough in an area where it consistently adopts a deferential and procedural approach. If the Court wants to return greater responsibility to domestic authorities and limit its review to a procedural one in all but the most exceptional of cases, then this review should be sufficiently exacting to ensure at least procedural compliance with Convention standards.

Speaking to a reporter from El País following the Court’s ruling in Sharifi, Mr Sharifi’s lawyer, Eddie Rosenberg Khawaje, commented that the Danish courts ‘do a very delicate balancing act and work on the borderline of what does or does not infringe human rights.’ He claimed that there would continue to be decisions that fall on the wrong side of the scale and noted that in light of pending cases ‘we can expect more judgments condemning Denmark this coming year.’ It will be interesting to see if the Court continues to apply its usual deferential, procedural approach in these cases and whether future rulings will clarify further what is required for it to substitute its assessment for that of the domestic courts. Regardless, the rulings in Sharifi and Noorzae may provide some reassurance for those who worry that an undue focus on procedure could lead the Court down an excessively deferential path. There are some cases – even against generally Convention compliant states – where a subsidiary Court will nonetheless find that a measure goes too far.

[1] These cases were identified through the use of the ‘advanced search’ function on HUDOC. The search was limited to judgments on the merits. Grand Chamber, Chamber and Committee judgment were included. In the ‘keywords’ section, the search was limited to cases on expulsion under Article 8. The search returned 65 results. Two of these judgments were excluded from my analysis: in D and others v Romania, Article 8 was not applied while S.J. and Belgium was struck out of the list. The search was carried out on the 19/10/2023.