February 25, 2020

By Ruben Wissing (Ghent University)

On 13 February, the Grand Chamber rendered a long awaited judgment, meandering over more than one hundred pages, in the N.D. and N.T case on the push-back practices against migrants at the Moroccan-Spanish border fence surrounding the city of Melilla – the so-called devoluciones en caliente or ‘hot returns’ by the Spanish border police. The Court did not qualify them as collective expulsions, thus acquitting Spain of having violated Art. 4 of Protocol No. 4. However, the specific circumstances of the case, as well as the absence of an examination of the principle of non-refoulement, have been ultimately decisive for the outcome of this case, thus restricting the extent to which the Court’s findings can be generalised to similar practices at the EU external borders.

Facts

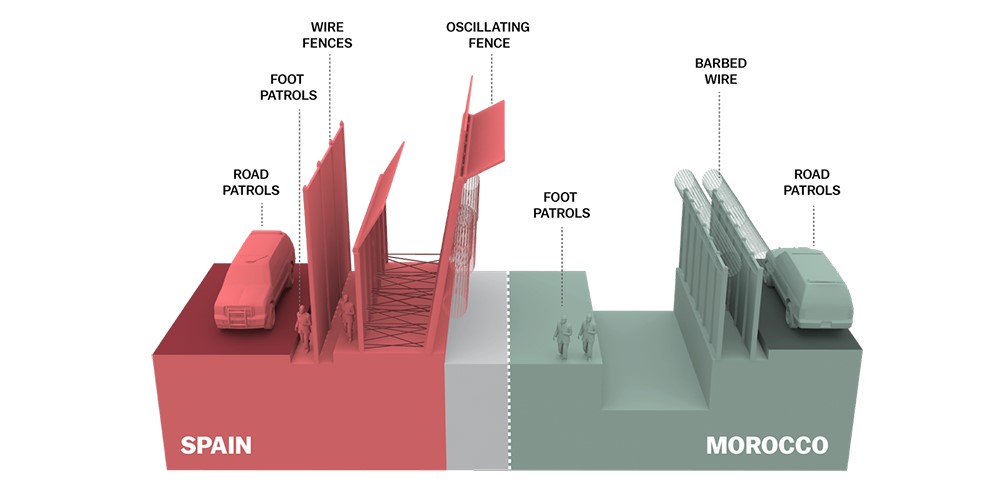

The two applicants, N.D. from Mali and N.T. from Cote d’Ivoire had attempted to enter the Spanish enclave of Melilla illegally on 13 August 2014 by scaling the fences. They were among about 75 sub-Saharan migrants (of an original group of about 600) who managed to get past the Moroccan police and over the outer fence and to reach the top of the inner (third) fence. The Spanish Guardia Civil helped them to get down on the Spanish side, apprehended them and handed them over to the Moroccan authorities without any identification procedure or notification of a formal decision (§§24-25). The practice was only posteriorly legalised by the introduction of Spain’s Institutional Law 4/2015 of 30 March 2015.

Later, N.D. and N.T. succeeded in entering Spanish territory by climbing the fences, on 9 December 2014 and 23 October 2014 respectively. Both got an expulsion order, which they appealed against, and were transferred to the mainland. N.D applied for international protection, which was refused and his request for review rejected. He was subsequently returned to Mali on 31 March 2015; his appeal was later declared inadmissible. N.T. did not apply for asylum and his appeal against his expulsion was dismissed. He was released after 60 days of detention and currently lives in Spain (§§28-30).

(c) El País

The judgment

The Court straightforwardly deals with the issue of jurisdiction – even more so than it had done in its Chamber judgment of 3 October 2017, where it still elaborated on the question of effective control. It does not accept any rebuttal of the ‘presumption of competence’ for facts that took place on Spanish territory. The Court dismisses the Spanish unilateral legal fiction of an ‘operational border’ outside its jurisdiction, as well as any other exceptional circumstances related to a migration influx that would restrict the effective exercise of the State’s authority, and thus limit its jurisdiction (§§104-110).

As to the merits of the case, the Grand Chamber was restricted to evaluating the prohibition of collective expulsions (Art. 4 Prot. 4) and the right to an effective remedy. Contrary to the Chamber judgment, no violation of the Convention rights was found.

The Court accepts that an expulsion in the sense of Art. 4 Prot. 4 has taken place, but not that it had a collective character. It first confirms the autonomous interpretation of the term ‘expulsion’ at land borders it had previously established in its case law related to border crossings at sea (Hirsi Jamaa, Sharifi, Khlaifia) (§187), giving it the generic meaning from international law: any formal act or conduct of the State that compels an alien to leave the territory (Art. 2 ILC Draft Articles on the Expulsion of Aliens) (§176). The Court reaffirms that States’ have a sovereign right to manage and control their borders (§167), but that this may not render the individual rights under the Convention inoperative and ineffective – in particular Art. 3 and Art. 4 Prot. 4, which have the same scope (§171). According to the Court, the term ‘expulsion’ includes national non-admission practices, in any situation under the jurisdiction of State, including where protection needs have not been examined yet (§186), and irrespective of any formal restrictions in national or EU law (§184). These principles thus apply to refugees and asylum-seekers, but also to other aliens unlawfully present in the territory (§181), as in the present case (§190).

The Court qualifies the collective character of an expulsion, also referring to its earlier jurisprudence (Khlaifia), as “the absence of a reasonable and objective examination of the particular case of each individual alien of the group” (§195). Such an individualised examination demands a genuine and effective possibility for submitting arguments and their appropriate examination by the authorities (§199). Unlike an Art. 3 ECHR complaint, where also substantial risks of ill treatment are to be assessed, an Art. 4 Prot. 4 complaint only demands an evaluation of procedural conditions, taking into account the particular circumstances and the general context of the expulsion at that time (§197), including the own conduct of the alien (§200).

In order to render Convention rights effective under these specific circumstances at the external EU borders, the Court finds that genuine and effective legal entry procedures have to be made available, which should allow for protection applications (§209). States may then require would-be migrants in need of protection to use those procedures and refuse entry to those who fail to do so without ‘cogent reasons’ (§210). The Court accepts the entry procedures provided for in Spanish law to be actually available and effectively accessible, in particular the possibility to lodge an asylum application at the Moroccan side of the Melilla border crossing in Beni Enzar (cfr. Section 21 of Law 12/2009, §213), besides the specific urgent admission procedure at Spanish embassies and consulates in third countries, such as the one in the nearby city of Nador (cfr. Section 38 of Law 12/2009, §§223, 227). It dismisses reports about the limited accessibility or effectiveness of these procedure at that time and racial profiling by the Moroccan police against sub-Saharan migrants, as insufficiently substantiated, beyond the responsibility of the Spanish authorities, or irrelevant due to the inadmissibility of the Art. 3 complaint (§§214-218, 225-226).

Since Art. 4 Prot. 4 does not imply a general duty for States to bring persons under its jurisdiction who claim protection under the Convention, the Court considers it to be attributable to N.D. and N.T.’s own conduct that their potential individual arguments were never submitted or examined and that no individual removal decision was taken. They had no cogent reasons for not having used the appropriate legal entry procedures. Instead they had entered irregularly at an unauthorised location, taking advantage of the group’s large number and use of force, thereby endangering public safety. They had “behaved badly”, according to the Court, which suffices for the State not to be required to further individualise its border expulsion procedures, without this violating Art. 4 Prot. 4 (§§ 201, 220, 231).

The Court concludes by reiterating that this does not alter the obligation of States to protect their borders in a manner compliant with Convention rights, highlighting in particular the principle of non-refoulement (§232).

Finally, the Court also dismisses the alleged violation of Art. 13 ECHR, in conjunction with the prohibition of collective expulsions. The fact that the State did not make available a legal remedy is accepted by the Court with a similar motivation: because the applicants failed to abide by the rules, and the substantial Art. 3 claim regarding the refoulement risk to Morocco had already been dismissed (§§242-243).

Comment

With the N.D. and N.T. judgement, the Court condones a deplorable State practice of violent policing, fencing and push-backs of migrants at the EU borders. In his concurring opinion, judge Pejchal, rather chillingly, suggests to justify this by excluding the Court’s competence for non-Europeans who suffered rights violations after first having migrated for causes they did not previously address at their own regional human rights courts (concurring opinion, p.107, last al.).

Nonetheless, to correctly assess the significance of this judgement, one also has to acknowledge that the Court does not, as some had feared, deliver a general endorsement of push-back policies at the EU external borders. It describes some very specific conditions under which governments might be excused from individualised processing at their external borders, namely: (1) the provision in law of entry procedures at the border or in transit States that are effectively accessible to migrants in need of protection; (2) the absence of cogent reasons on the part of the would-be migrant for not using those procedures; and (3) aggravating circumstances (a disruptive situation, endangering public safety) that are attributable to the migrant (such as taking advantage of a group’s great number and use of force) (§§201, 209-211, 239).

Such a threshold will not be easily reached in most EU external border contexts. Spain is likely to be an exception among external Member States in providing for some safe and legal pathways for refugees in its law. It is, however, surprising how easily the Court is satisfied with the presumed effectiveness of those procedures in practice. Reliable reports mentioned in the judgement, such as the ones of the Commissioner for Human Rights (§143) or UNHCR (§155) sketch a less positive image of the practical accessibility of the border crossing point at Beni Enzar for sub-Saharans. And the urgent transfer procedure is not very likely to be an actual alternative for an effective asylum procedure (as the Court somewhat admits in §226): from the text of Law 12/2009 (Section 38) it is clear that it is only accessible for persons whose physical integrity is at risk – thus adding an extra condition to the refugee definition or Art. 3 – and does not apply to nationals of the location of the embassy – thus demanding persons at risk to first cross an international border. Consequently, this procedure is not accessible for e.g. Moroccans in Morocco, contrary to the example given by the Court (§225), not for refugees who don’t run an immediate physical risk. Also, the suggested nearby city of Nador is in practice a notorious no go zone for sub-Saharans (as reported by Amnesty International and national NGO GADEM).

Further, it remains unclear how, in practice, a border authority should establish the ‘cogent reasons’ a would-be migrant might have for choosing an unauthorised entry attempt over legal entry alternatives, without at least some identification procedure and individualised examination at the borders. Might the Court have missed this point due to the very specific situation of the applicants in this particular case? After all, both eventually did enter Spain, where N.D. applied for asylum but was refused and N.T. chose not to apply for it although he had the material possibility to do so. It had thus been ascertained post factum that they did not run a substantial risk of inhumane treatment in their country of origin. Could this conclusion that N.D. and N.T. are “not refugees” have brought the judges to accept that the purely procedural aspects of article 4 Prot. No. 4 are not necessary anymore to guarantee a substantial protection (cfr. the evaluation of the equally purely procedural right to an effective remedy, §240)? Although the Court dismissed the subsequent proceedings as irrelevant for the evaluation of the disputed expulsion (§121), it seems to have taken into account the outcome of exactly these proceedings to evaluate whether N.D. and N.T. had good reasons, or not, to climb the fence. Would the Court have demanded more procedural scrutiny in the case of migrants who did not re-enter the EU and had their asylum claim assessed? One can only guess since, unlike N.D. and N.T., migrants in such situation have not found their way to a Strasbourg procedure yet.

The limited scope of the judgement also lays here: some push-back practices might under strict conditions not amount to collective expulsions, but this does not at all exclude them from potentially violating the principle of non-refoulement. It is remarkable how the Court stresses this explicitly in its conclusion: border control practices should continue to be Art. 3 sensitive (§232). In this case, the original complaint of an Art. 3 violation was declared inadmissible by the preliminary 2015 decision of the Chamber of the Third Section (§§3-4), because the applicants allegedly had not claimed inhumane treatment by the Spanish authorities during the expulsion (“lors de leurs expulsion” in the original French decision of 7 July 2015, §15). As a consequence no prospective evaluation of the applicants’ situation in Morocco following an expulsion has been made neither. This is striking because the applicants had explicitly claimed to be at risk of ill treatment there (GC §3, 2015 decision §§3-6), and reference was repeatedly made to the use of force and refusal of medical aid and lack of any procedural scrutiny by the Moroccan authorities – not only in the preliminary decision of 7 July 2015 (§§3-7), but also in the Court’s own representation of the facts (§§25-26), and in the submitted reports on generalised ill-treatment of sub-Saharans (§§68, 158). Also the Human Rights Committee in its 2016 periodical report on Morocco mentions excessive use of force, collective expulsions, arbitrary arrests and a deficient asylum system. It is at odds with the Courts own refoulement case law not to take the situation in the transit country to where the person is expulsed into account (M.S.S., Hirsi Jamaa), but this in itself is no reason yet to lament the ECtHR departing from the procedural and substantive non-refoulement safeguards established in its Art. 3 jurisprudence.

Conclusion

The Court has decided lightly that the hot returns by the Spanish authorities are not collective in nature, given the disputable assessment of the effective availability of legal entry alternatives. States less benevolent towards migrant’s rights might be given the impression that they are free to push asylum seekers back at the border without any procedural guarantee.

The true impact of this judgment will, however, be less dramatic and more nuanced:

The Court, firstly, has confirmed the broad scope it attaches to the concept of expulsion, to include all admission practices at land borders, and from which States will find it difficult to escape responsibility for. Secondly, the Court has identified strict conditions for expulsions at the border, including a principled requirement of safe and legal entry procedures to be provided for in the context of an increasingly closed external border regime, such as the one the EU is rolling out.

Although States might still think the Court gives them some leeway to organize push-back practices, summary expulsions will still be in violation of other human rights provisions – or of EU law, such as the Return or Asylum Procedures Directive. N.D. and N.T. is not a case in which the right to asylum as such was at stake, and not even its closest cognate in the Convention, the principle of non-refoulement under Art. 3 – which gives a much broader protection to all would-be migrants under the broad jurisdiction of the State at its borders and prohibits all forcible returns without prior substantive risk assessment. It does not seem farfetched to say that, if the Grand Chamber were to have judged the ‘hot return’ while the Art. 3 complaint was still pending – more likely in a situation where the applicants had not managed to enter the EU afterwards – it would have decided that a violation had taken place.

Ruben Wissing is a PhD researcher at the Migration Law research group of Ghent University, Belgium, on the project ‘Safe with the neighbours? Refugee protection and EU external migration policy in Turkey and Morocco’. He is a member of the Human Rights Centre at the Faculty of Law and Criminology and the interfaculty CESSMIR (Centre for the Social Study of Migration and Refugees).

1 Trackback